If you made a list of the greatest jazz musicians of all time and then a list of the happiest human beings of all time, you wouldn't have to worry much about overlap.

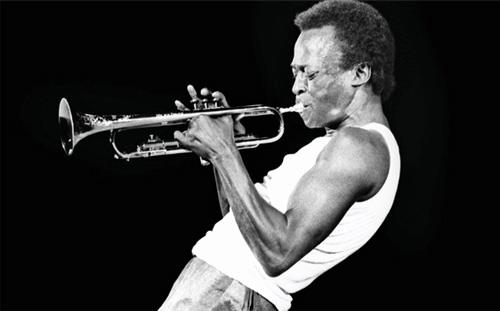

The new PBS American Masters film Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool, which premieres Tuesday at 9 p.m. ET (check local listings), makes it clear that for all this trumpet master's musical skill and influence, his life was full of jagged edges on which he often had trouble dancing.

Veteran filmmaker Stanley Nelson rounds up A-list jazz musicians like Ron Carter, Wayne Shorter, and Herbie Hancock to praise Davis' talent and confirm the reverence in which the jazz world still holds him 29 years after his death.

Carter recalls how Davis would bring musicians into a session, or onto a live stage, and tell them that the first notes of a song were a starting point, not a blueprint.

Some of his best recordings, his fellow musicians say, sprang from his conviction that a band could be a democracy, where everyone had a voice in determining where a song would go.

Davis wrote in his 1990 autobiography, parts of which are read as voiceovers here in a gravely Davis-style tone by Carl Lumbly, that some musicians have an instinct for creativity, and some don't.

He looked for those who did, and when he found them, he let them explore.

At the same time, that didn't make him everyone's gregarious pal. His former bandmates also remember that he could be as distant with them as he sometimes was with his audiences.

No one ever nominated Miles Davis for Mr. Congeniality, and while Birth of the Cool doesn't focus on his anti-social behavior, it gets an extensive report from his first wife, Frances Taylor, on the less admirable side of his personality.

She was a world-class ballerina who had landed a job in the original Broadway production of West Side Story. He was jealous of her being around other men, so after they married, he told her she had to drop her career and become a housewife.

She regretted it, she says, but she did. Then Davis' drinking and cocaine use intensified, his moods became more erratic, and eventually, he started beating her. She finally filed for divorce.

Looking back, she says, she marvels at how someone who could create such sublime music "could also have this other side."

Nelson follows the whole roller coaster of Davis' career, which started early and high. One of his first jobs was with Billy Eckstine's band, where, for a while, Davis was playing alongside Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker – meaning much of the future of jazz was on stage every night backing Eckstine's smooth classic ballads.

We get details on how Davis created Kind of Blue, the best-selling jazz album of all time. We hear about the drugs and get strong hints of the anger. We see how he stretched himself in the late '60s by working with rock and Latino musicians like Carlos Santana.

We see the buildup to his burnout, how from 1975 to 1980, he never picked up his trumpet, focusing instead on putting himself back together.

He returned a little more open and musically ambitious. He also hadn't shaken all the demons.

He still liked expensive cars, especially Ferraris, and for a time in the 1980s, he was married to actress Cicely Tyson. During part of that marriage, he also had an affair with artist Joanne Gelbard, who was his partner as he got into painting.

He was 65 when he died. Gelbard, who, along with Tyson, is interviewed here, remembers him telling her that the gods don't punish people by not giving them what they want. The gods punish people, he said, by giving them what they want and then not giving them time.

Music fans who remember Davis as a genius musician and a cold human being will be heartened by the number of photos in Birth of the Cool that show Davis smiling, and the number of musicians who suggest he found pleasure in his work.

But he clearly wasn't even on the waiting list for happiest human beings of all time.