The apparent suicide of comedian/actor Robin Williams has affected people more personally than any celebrity death I can recall. It’s not just that the tweets of the rich and famous who worked with him or knew him socially are warmer, sadder and more genuine sounding than we usually see, it’s that everyday folks with whom I speak or communicate with via Facebook act as though they’ve lost a family member.

A big part of that, no doubt, has to do with Williams’ ubiquity. He’s deeply embedded in the consciousness of at least two generations. After he catapulted to national attention in the ABC sitcom Mork & Mindy in 1978, he was seemingly everywhere, starring in movies as a hyperkinetic Vietnam disc jockey, a nanny in drag, a schizophrenic street person, doing voice work for Disney animations and stand-up specials for HBO, enlivening talk shows, and co-hosting Comic Relief fundraisers with his super-friends Billy Crystal and Whoopi Goldberg.

A big part of that, no doubt, has to do with Williams’ ubiquity. He’s deeply embedded in the consciousness of at least two generations. After he catapulted to national attention in the ABC sitcom Mork & Mindy in 1978, he was seemingly everywhere, starring in movies as a hyperkinetic Vietnam disc jockey, a nanny in drag, a schizophrenic street person, doing voice work for Disney animations and stand-up specials for HBO, enlivening talk shows, and co-hosting Comic Relief fundraisers with his super-friends Billy Crystal and Whoopi Goldberg.

But the strong reaction to Williams’ death also speaks to his warmth and vulnerability. His comedy was often manic but seldom if ever mean. The title of his first comedy album, Reality…What a Concept, conveyed his bemusement with the human condition, his included. His characters, even the villains he occasionally played so chillingly, had something touching about them. And few celebrities have been as open about their weaknesses and addictions.

Neither of Williams’ two prime-time series, Mork and this past season’s The Crazy Ones on CBS, won a Peabody Award. He was, however, an integral part of two Peabody-winning specials that remind us of both his range and his heart: the post-9/11 Tribute to Heroes telethon and HBO’s Dear America: Letters Home from Vietnam. He was one of the celebrity readers.

Like most people, I can’t begin to count the occasions on which Williams made me laugh – Tonight Show appearances, Good Morning Vietnam, Jumanji, Aladdin, Mork. And speaking of the latter, I will never forget my only in-person encounter with Williams.

In the summer of 1978, ABC trotted Williams out at an evening event for a herd of TV critics visiting Los Angeles for fall-season press previews. Williams had had very limited TV exposure up to that point – a couple of cameos on Richard Pryor’s short-lived 1977 variety show, a guest shot on Eight Is Enough. He’d done a version of Mork, the alien from planet Ork, in a Happy Days episode the previous spring, but few if any critics were monitoring Fonzie and company on a weekly basis at that point.

In the summer of 1978, ABC trotted Williams out at an evening event for a herd of TV critics visiting Los Angeles for fall-season press previews. Williams had had very limited TV exposure up to that point – a couple of cameos on Richard Pryor’s short-lived 1977 variety show, a guest shot on Eight Is Enough. He’d done a version of Mork, the alien from planet Ork, in a Happy Days episode the previous spring, but few if any critics were monitoring Fonzie and company on a weekly basis at that point.

Williams thus stepped on stage that night as an almost totally unknown commodity. And what we critics experienced was an odd sensation: tumultuous merriment combined with awe.

Built like a collegiate wrestler, trained as a street mime, programmed like a Univac computer with cultural knowledge that spanned from Sigmund Freud to Fay Wray to Elmer Fudd, with a data-retrieval speed that suggested a microchip not yet invented, Williams was an amazing comedy machine. He was like Jonathan Winters, his improv hero, on a concentrated caffeine drink, also not yet invented.

He was only 27, but all his trademark shtick – the voices, the movie, political and literary references, the social awareness, joined and juxtaposed with staggering quickness – was all there. He was fully formed.

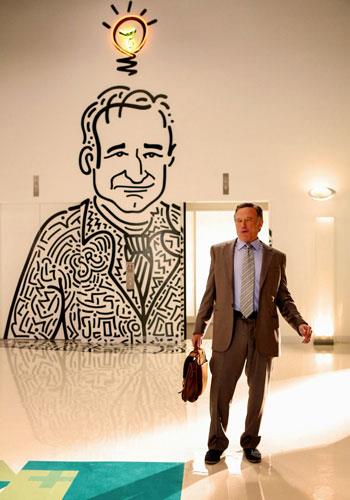

When I subsequently wrote about his exhilarating stand-up and the interview session that followed it for the fall TV preview section of The Orlando Sentinel, we were at a loss at first to come up with an illustration that did this wunderkind, this comedic cyclotron, full justice. Then one of our graphic designers, Sarah Keyes, noticed that ABC had provided several promotional photos of Williams in his soon-to-be trademark Mork suspenders doing stand-up. His arms were at his sides, his hands outstretched, palms up, as if to say, “Can you believe this?” And in each photo his facial expression was different.

When I subsequently wrote about his exhilarating stand-up and the interview session that followed it for the fall TV preview section of The Orlando Sentinel, we were at a loss at first to come up with an illustration that did this wunderkind, this comedic cyclotron, full justice. Then one of our graphic designers, Sarah Keyes, noticed that ABC had provided several promotional photos of Williams in his soon-to-be trademark Mork suspenders doing stand-up. His arms were at his sides, his hands outstretched, palms up, as if to say, “Can you believe this?” And in each photo his facial expression was different.

Sarah’s pre-Photoshop brainstorm, based on reading my attempts to describe Williams’ hyper-animated mind, was to cut out three of the heads and paste them onto the full length photo. Williams thus appeared to be juggling multiple variations of himself like so many bowling balls.

Robin Williams kept his phenomenal juggling act going for 36 more years, showing us so many faces, so many sides, all the while battling the downsides of such prodigious creative gifts. We can be thankful for that, even as we mourn.