Forty-plus years of covering television have yielded countless close encounters with stars of the first magnitude.

Many are now deceased, but their bodies of work still breathe.

So rather than relegate these experiences to the dustbin, I'm periodically bringing some of them back alive. For me, they're gifts that keep on giving. This is the second in an occasional series.

***********

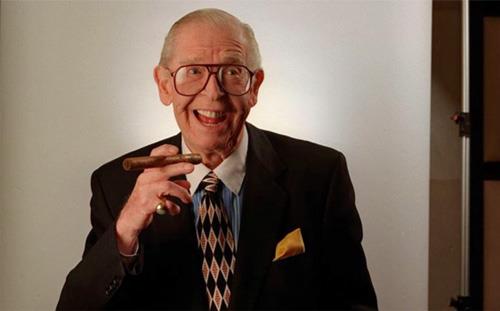

Alternately known as "Uncle Miltie" or "Mr. Television," Mendel Berlinger (Milton Berle) lived until age 93 and likely got off one last one-liner before succumbing in 2002.

"Wherever it may be, any place I can get on and talk and be funny, whether it's five people in an audience or in a drawing room in your house, just call me," he told his interviewer in the summer of 1981. Or if you don't call me, I'll get up. Because that's the way I'm built. I can't help it."

Our venue was Dallas' now long-defunct Granny's Dinner Playhouse, where patrons would dive into a buffet line before settling in for that night's headliner. Berle was doing his standup act, and we talked off-and-on during breaks from rehearsal. He sliced his 73rd birthday cake during the multi-night engagement.

"Somebody asked me, 'What're you doin' at Granny's?' Such a thing to ask. I wanna work! It sounds like a cliché, but I work to live, and I live to work. I could've retired 25 years ago, but maybe I wouldn't be living today."

No one was bigger than Berle in TV's infancy. Before Lucy and Desi, his Texaco Star Theatre variety hour became the nation's first small-screen sensation back in 1948. As the first mega-star of this new medium, Berle was credited with selling thousands of TV sets to people who suddenly couldn't get through Tuesday nights without Uncle Miltie, who often appeared in drag.

Your friendly correspondent was born in the year Texaco Star Theatre premiered. Just five years later, it ran out of gas when Berle's sponsor dropped out. He never hit it that big again, but never went away either. His last big chance as a variety show host lasted just 17 weeks on ABC in 1966.

"That I was very bitter about," Berle said. "I'll tell ya why. Because they didn't give it a shot. The show was ahead of its time because it preceded Laugh-In, which was the same kind of show. We had the blackouts, cross-outs, lots of stars. But they didn't give it a chance."

Berle frequently spoke in a confidential tone of voice, as if to say, "Listen, kid, this is something I don't tell just anybody." His famous smile often was simply a baring of the famous teeth. The upper lip rolled up like a window shade to show off what were now a polished set of dentures. He occasionally wore his glasses on his forehead, and his gray hair broke out in tufts after he worked up a sweat while doing a little dancing. Or coaching the band. Or triple-checking the sound system. Or flirting with his supporting act, Dallas singer Cynthia Scott.

Above all, the show absolutely must go on.

"You're an actor. The spotlight hits ya, and ya give 'em a smile," Berle said, once again leaning in close. "See, if you're born in the business, when you hear that applause and laughter, it does something to you. For that hour or so you're onstage, your mind is away from everything. It's like, carry on I must. And I do…I'm here to do crazy, escapist entertainment. That's all I want to give them."

Which he did on opening night, striding onstage in a blue blazer, high water gray slacks, and a powder blue button-down shirt. "You want me, you love me," Berle assured his audience before taking a few well-practiced shots.

"I remember you, lady. You heckled me 20 years ago. I never forget a dress."

"I've got some friends here celebrating their 25th anniversary. They're sitting there with their 26-year-old son."

"Throw another log on the air-conditioner, will ya?"

The one-liners, the delivery, and the trademark smirks. Everything worked, which Berle knew going in.

During our earlier interview, I had the temerity to ask him, "Are you as sharp as you ever were?"

"Sharper," he said.