What he said himself was his only desire was to walk down the street and have people say, “there goes the greatest hitter who ever lived.”

— Bob Costas, sportscaster, from American Masters: “Ted Williams”

I was too young for Ted Williams to be a personal hero of mine growing up in Massachusetts. He was already at the end of his legendary career, but my father and two older brothers regaled me with many stories about his prodigious talents as a hitter.

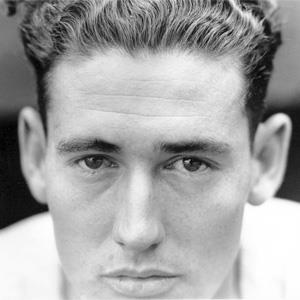

Baseball was still arguably the national pastime when Ted Williams (right) hit a home run on his last at-bat on September 28, 1960. As I was a native New Englander and a lifelong Red Sox fan, Williams occupied a space in my young imagination alongside Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, and my favorite baseball player at the time, the incomparable Willie Mays.

Many of the greatest ballplayers in those days had colorful nicknames. Willie was “The Say Hey Kid.” According to the argot of baseball, he was a “five-tool” phenom. He hit for a high average; hit with tremendous power; ran the bases with speed and style; threw out opposing base runners while deep in the outfield; and fielded his position with exceptional range and grace. In comparison, Ted Williams, also nicknamed “The Kid” (his favorite), the “Splendid Splinter,” “The Thumper,” “Teddy Ballgame,” and the “Greatest Hitter Who Ever Lived,” excelled at the first two tools and was admittedly average, at best, in enacting the last three skills.

But boy could Ted hit!

Monday, July 23, at 9 p.m. ET (check local listings), PBS’s 32-year-old multiple Emmy-award-winning flagship series, American Masters will devote a prime-time episode to “Ted Williams: ‘The Greatest Hitter Who Ever Lived.'" Beginning on July 24 and thereafter, the one-hour program will also be available here for streaming.

The film was produced, directed, and written by Nick Davis and co-produced by Major League Baseball, Worcester (MA)-born composer Albert M. Tapper, and Big Papi Productions (the company owned by recently retired Red Sox slugger, David Ortiz). Suffice it to say that this documentary was a labor of love for those involved.

Filmmaking is the family business for Nick Davis whose father is Academy Award-winning documentarist, Peter Davis (Hearts and Minds), his paternal grandparents screenwriters were Frank Davis and Tess Slesinger (A Tree Grows in Brooklyn), and his maternal grandfather was Oscar-winning screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz (Citizen Kane).

Greenlighting an episode on Ted Williams is somewhat of an anomaly for American Masters since the series is “devoted to America’s greatest native-born and adopted artists,” including biographical documentaries on novelists, poets, dramatists, musicians, filmmakers, actors and actresses, visual and performing artists. Of the 240-odd episodes so far, Williams is only the third athlete. The other two are tennis pioneers, Billie Jean King in 2013 and Althea Gibson in 2015.

The choice of Ted Williams makes immediate sense in the first three minutes of the program with a concise 97-second scene that establishes the mythic aura that springs up around this prodigy in just his 1939 rookie season when he seemed to emerge out of nowhere and set the baseball world on fire. His greatness as a hitter has long been acknowledged by old-timers, contemporaries, and the generations of major league baseball players who came after him. For example, current Cincinnati Reds all-star, Joey Votto, describes offscreen that “his swing was a work of art.” Former Red Sox, Yankee, and Tampa Bay Devil Ray Hall-of-Fame (HOF) third baseman, Wade Boggs, confirms onscreen that “his bat was a brush and Fenway Park was the canvas.”

The documentary is narrated by Emmy award-winning actor and baseball enthusiast, Jon Hamm, and features a wide array of personal and professional witnesses including Ted’s daughter, Claudia, broadcasters Bob Costas and the late Dick Enberg, and former Boston Globe journalists and leading Williams’ biographers, Ben Bradlee Jr. (The Kid: The Immortal Life of Ted Williams) and Leigh Montville (Ted Williams: The Biography of an American Hero), among others.

Like baseball itself, “Ted Williams: ‘The Greatest Hitter Who Ever Lived’” is a dramatic mixture of reality and myth that is always struggling to find the often difficult, stubborn, and salty-mouthed individual hidden underneath the sometimes apocryphal stories. For instance, Ted bristled at being described as a kind of “Natural” à la Roy Hobbs from Bernard Malamud’s debut novel (1952) as the film underscores the enormous amount of time, hard work, and dedication he devoted to hitting with an almost OCD-like determination to the exclusion of everything else. As Bradlee recounts him saying, “as a husband and a father, I struck out.”

The film, too, depicts how Ted grew up in “abject poverty” in San Diego. His father, Sam, was a soldier, failed photographer, and chronic drunk of Welsh-Irish heritage; his mother, May (Venzor) Williams was a Mexican-born Salvation Army worker whose nickname was the “Angel of Tijuana”; and his brother, Danny, grew up to be a small-time criminal. He rarely spoke about his family, and as the program reveals, “he actively concealed he was Mexican American.”

Claudia explains how her father had “a boiling anger and he used it playing baseball.” Before Tom Brady had Peyton Manning to measure himself against, Larry Bird had Ervin “Magic” Johnson; Bill Russell had Wilt Chamberlain; Ted had the “Yankee Clipper,” “Joltin’ Joe” DiMaggio (left, with Williams). They became forever linked from the 1941 baseball season onward when DiMaggio went on his unassailable 56-game hitting streak, and Williams became the last major leaguer to hit over .400. The documentary shows how he went six-for-eight in a doubleheader on the last day of the season to finish with an average of 406.

Joe and Ted were a study in contrasts. DiMaggio was regal, calculating, and circumspect; Williams was a rough-around-the-edges innocent, volatile, and always wore his emotions on his sleeve. Both made each other better, though, and ended up being first-ballot Hall-of-Famers. Williams' complexity as a person was on full display during his acceptance speech to the HOF in 1966. He was a believer in the American Dream and a social conservative in almost every respect, except when it came to the matter of civil rights:

"Baseball gives every American boy a chance to excel. Not just to be as good as someone else, but to be better than someone else . . . I hope someday the names of Satchel Paige (left) and Josh Gibson (left) in some way can be added as a symbol of the great Negro players who are not here only because they weren’t given the chance."

The documentary suggests that the discrimination that Ted experienced as a boy in San Diego, and the inferiority and resentment he felt throughout his life because of his racial-ethnic background, was at the root of his appeal on behalf of the great African-American ballplayers who were excluded from the game until Jackie Robinson heroically broke the color line in 1947.

In retrospect, Ted Williams is indeed the first Latino player ever elected to the HOF, even though most people didn’t know it at the time. He was a throwback character in so many ways. Bob Costas describes him as “the guy who John Wayne play[ed] in all those movies.” By the time of his HOF induction, his words had enough gravitas to carry special weight in baseball circles. (Satchel Paige was eventually elected into the hall in 1971; Josh Gibson in 1972.)

Baseball isn’t as central to American culture as it once was when it served along with the armed services as a primary venue for integrating U.S. society. Ted Williams was in his prime then during the late 1940s and early 1950s. As phenomenal as his accomplishments were as a player, Nick Davis’ film points out in the first scene that Ted missed nearly five of his best years as a baseball player, serving three in World War II and two in Korea as a fighter pilot. Without this lost time, his hitting numbers probably would have approximated Babe Ruth’s (right). Joey Votto concludes, “Babe and Ted—neck and neck—nobody’s close.” Wade Boogs is even more definitive: “Ted Williams is the greatest hitter who ever lived. Not an argument.”

The greatest players now—Mike Trout, José Altuve, Mookie Betts, and yes, Joey Votto—are relatively unknown even today when compared to someone like Ted Williams who has been dead for 16 years and retired from the game for 58 years. My main criticism of this program is that the funders at American Masters only allotted an hour for a subject as complex as Williams when other episodes in the series have lasted two, four, and as much as six hours.

Still, watching “Ted Williams: ‘The Greatest Hitter Who Ever Lived’” is well worth the time as an introduction to this creative and enigmatic cultural exemplar from the mid-20th century. He was an American original whose obsessive pursuit of excellence elevated the art of hitting to heights that are still emulated and admired today.