Today's culture is so celeb-saturated that we know everything about everybody famous, and start to wish we didn't. Yet "regular" people have almost ceased to exist. Every ordinary American now seems to be appearing on a "reality" show or rehearsing for one. The boy and girl next door are so ready for their close-up that we only see "unaffected" when an actor affects in it performance.

That's why I'm so addicted to Mill Creek's four new budget DVD sets of vintage game shows. They provide snapshots of both the famous and the nameless back when television was younger and people were less intense about it. The guest stars feel more glittery yet more genuine, and the ordinary players feel not self-consciously "real" but truly authentic.

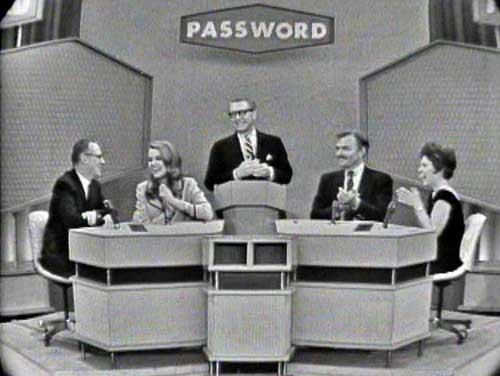

Password in its 1960s prime-time version proves the pinnacle in this sociological spectator sport -- and it's also an engagingly timeless game, at least in the straightforward way it's played in the 30 episodes in The Best of Password. (Mill Creek's new 3-disc set is the re-release of a 2008 BCI set that quickly disappeared from shelves.)

Two celebs pair up with two contestants trying to guess a secret word. One member has to give the other member one-word clues, as teams alternate, to make his/her partner guess it before the other team does. That's it. It's the Wheel of Fortune of its day in its simplicity and its play-along irresistibility. But it's also more elegantly sophisticated. No gimmicky prop wheel or light-up letters. (And, thankfully, no Vanna.) No contestant squealing or audience shrieking. Plain set, plain desk, even a plain host: laid-back Allen Ludden, who comes across charming and witty simply by remaining in the moment.

The stars and the players are just as plain -- people coming direct from the Manhattan studio to your living room, with a relaxed amiability, without seeming intent on presenting a slick image. Sammy Davis Jr. bops all over the place, too wired to sit still. Jane Fonda, barely out of Vassar and still lacking a public persona, nervously tries too hard to play well. Johnny Carson, pre-Tonight Show fame, comes off as an up-and-comer, reserved yet coolly self-assured. A young Woody Allen is awkwardly, adorably Woodyish. Betty White, who'd just gotten married to host Ludden, looks about to jump his bones any second. (Some reputations are well-earned.)

It feels timeless because there's so little production to it. Just black-and-white videotape, without frantic jumpcuts or flashing graphics, with a static pace and quiet moments. Regular folks just act regular, and celebrities try hard to help and harder not to look dumb. Who knew young Nancy Sinatra was so sharp? Who expects Elizabeth Montgomery to digress with "God bless you" when an audience member sneezes?

There's a naivete and even a touch of raggedness to the proceedings -- small mistakes are left in -- yet there's also the opposite of the condescension today's TV often seems to feed us. Password trusts the audience to be at least as smart as the players -- which, of course, we are, shouting better clues at the screen than the celebs can come up with. It all feels adult and aspirational in a way that makes me wonder why some network doesn't try something as simple as this now. Talk about standing out in a frenzied marketplace.

For all the relative class of Password, I'm also endlessly fascinated by the naked conumerist greed celebrated in The Price Is Right, which the Mill Creek set serves up in two flavors through 26 episodes. Four episodes of the black-and-white '50s-'60s original are hosted by Bill Cullen, another genially laid-back everyguy, sitting on a spare set interviewing a panel of price-bidding everyman contestants clearly chosen for their slice-of-Americana appeal: giddy housewives, traveling salesmen, switchboard operators. (The other slice-of-life comes in the way these parades of "modern" products reflect their now-quaint era: rec-room "bachelor" bars, spinet organs, reel-to-reel "stereophonic" tape recorders.)

And then there's the Bob Barker version, seen here in all its nametags-and-Technicolor glory, from the 1972 premiere to 1975's first hourlong episode and then his 2007 finale week. Barker comes from a different host genus, being more smooth than affable, and Price itself has moved into the era of glossy production. The sets are gaudy color circuses, and the varied games are much more intricately devised than the earlier bidding contests. By this time, TV had decided it was desperate to KEEP us interested, as opposed to simply being interesting enough to watch. For me, here, there's less sociology to assess.

But there's plenty on display in Mill Creek's Match Game set, from the 1970s CBS color version with host Gene Rayburn leering over six randy celebs supposedly trying to match a sentence's missing word to that suggested by a contestant. But the show's focus, of course, quickly settled into celebs making as many double entendres as possible, while behaving as if rowdily drunk/stoned/gonzo.

With six celebs per show, Match Game relied on a regular roster of star nuts -- Charles Nelson Reilly, Brett Somers, Richard Dawson and other recurrent rowdies (Betty White, Fannie Flagg, Bill Daily) -- whose behavior would become legend. Reilly was bitchy, Somers was snotty, Dawson the "good" player who actually helped contestants win. But more fascinating are the visiting celebs -- from William Shatner to Jamie Lee Curtis -- who variously fit right in with the wildness, struggle to keep up, or seem baffled by it all. Who's stoned? Who's confused? Who isn't even sure where they are? Ah, the '70s.

(The Match Game set also includes the 1962 pilot of NBC's original and much calmer black-and-white daytime version, plus a Brett Somers interview and other extras.)

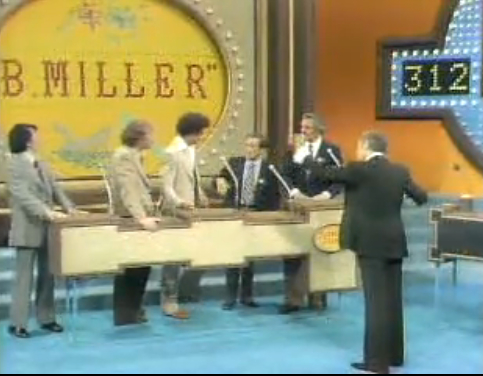

Dawson stars again by hosting his own show in Mill Creek's All-Star Family Feud set -- a veritable bounty of '70s star-sighting as the casts of two shows play each other, trying to match the most common responses to poll questions. Feud, too, was a loosey-goosey affair, and these All-Star episodes provide the added bonus of seeing stars outside their controlled habitats, interacting as themselves rather than their characters.

The competing casts include those from Dallas, Dukes of Hazzard, WKRP, Barney Miller and oldies like Gilligan's Island, Brady Bunch and Leave It to Beaver. There's even vintage soap from General Hospital. But the players aren't always their show's "stars." The Welcome Back, Kotter crew, for instance, features Mrs. Kotter and some late-run Sweathogs you forgot existed. (Nice names from Barney, though.)

Mill Creek's game show sets play today as more than just amusing viewing or nostalgic memories. They're little time capsules of past pop culture eras -- encapsulating their day in a way that I wonder whether any of our own TV shows will deliver decades later.

The password is . . . cool.

Also new on DVD:

The Patty Duke Show Season 2 -- These '60s familycom episodes hold up. Even better, a new featurette deconstructs how split-screen filming enabled the teenage Duke to play "identical cousins" Patty and Cathy.