[Bianculli here: Today at 4 p.m. ET, TCM presents a rare showing of an old movie that still works -- especially, contributing critic Eric Mink suggests, for journalists. The film is 1952's Deadline -- U.S.A., with an eerily timely message...]

Journalism wallows in one existential crisis after another. Take your pick: Internet technology is killing the news profession; the Great Recession is suffocating a business model already on life support; concentration of ownership is destroying media's vital competitive drive; the ethical vacuum around Fox News' success is sucking the lifeblood out of honorable news presentation. These days, you couldn't be blamed if you believed that the inherent short attention span of youth were a genetic mutation caused by cellphone radiation to the brain.

How startling, then, to discover not only a measure of reassurance about all this, but also some genuine wisdom, in a 58-year-old Hollywood movie.

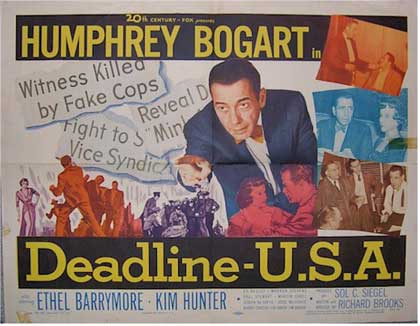

You can't hardly find 1952's Deadline -- U.S.A. It's not out on home video, DVD or VHS. Amazon, Netflix, Blockbuster, Red Box -- forget it.

Cable's Turner Classic Movies has a print in its archives, but the picture, written and directed by Richard Brooks, doesn't turn up much. A rare scheduled screening Wednesday at 4 p.m. (ET) is part of the channel's annual Summer Under the Stars focus on different actors each day in August. The movie appears on the day devoted to Ethel Barrymore.

Barrymore delivers a gleaming supporting performance in Deadline -- U.S.A. as Margaret Garrison, widow of the founder and owner of The Day, a great metropolitan newspaper in trouble. Garrison's distressed staff is led by managing editor Ed Hutcheson, played by an alternately sulking and furious Humphrey Bogart.

I managed to get hold of a reasonably decent copy last year and was stunned at how much I'd forgotten in the decades since I'd last seen it -- years before I'd ever worked for a newspaper.

The film is littered, of course, with newsroom markers that would have given it authenticity in 1952 but are long dead: clacking typewriters and wire service teletype machines, pneumatic tubes coughing pasted-up stories from copy desks to the composing room floor and back, headsets on re-write men taking phoned-in notes from reporters and instantly turning them into finished stories.

The film is littered, of course, with newsroom markers that would have given it authenticity in 1952 but are long dead: clacking typewriters and wire service teletype machines, pneumatic tubes coughing pasted-up stories from copy desks to the composing room floor and back, headsets on re-write men taking phoned-in notes from reporters and instantly turning them into finished stories.

There also is no shortage of familiar newsroom stereotypes -- a "tough-broad" woman reporter among them -- and fast talkers that put Aaron Sorkin's West Wing and Sports Night characters to shame. And, after hours, lots of alcohol at the local bar.

There's also a music score that's almost intolerably hokey in spots ("The Battle Hymn of the Republic"??!!) and enough dated wise-guy dialogue to set your eyes rolling for chunks of the film's 87 minutes.

But those glitches pale in comparison to the emotional pull of the movie's two interlocking stories:

First, Garrison's two daughters want to cash out their inheritance by selling The Day to a competitor who will shut it down. Their mother (Barrymore) doesn't want to sell, but she's outvoted.

At the same time, a well-connected hood is rigging elections, robbing the city blind and bumping off people with impunity. But he makes a big mistake when he has a snoopy reporter for The Day severely beaten up. That fires up Hutcheson, who also sees aggressive coverage as a way to generate enough public interest and pressure to kill the sale of the paper.

Bogart's Hutcheson delivers most of the impassioned passages about the news profession and why it's important. Remarkably, they still resonate today, notwithstanding the industry obits we see and read almost daily:

"The Day is more than a building," Hutcheson says during a court hearing into the validity of the sales contract for the paper. "It's people. It's 1,500 men and women whose skill, heart, brains and experience make a great newspaper possible. We don't own one stick of furniture in this company, but we, along with the 290,000 people who read this paper, have a vital interest in whether it lives or dies."

It hardly matters how the work of skilled, sensitive, smart, experienced news people gets to the public. People still hunger for it, and society still needs it. The real threat to the news profession, then, lies with frightened corporate executives who lack a commitment to what they're supposed to manage, and who lack the skill, sensitivity, intelligence and experience of the people who work for them.

Early in Deadline -- U.S.A., Hutcheson tries to shame Mrs. Garrison into defying her daughters. In the company's board room, Hutcheson invokes the newspaper's founding principles and points to a framed copy of its first edition hanging on the wall. Then he begins to recite, from memory, the statement published on the front page of that paper:

"This paper will fight for progress and reform, will never be satisfied merely with printing the news, will never be afraid to attack wrong, whether by predatory wealth or predatory poverty."

When I heard Bogart deliver those lines, an electrical jolt coursed through my spine. I had seen them before. I had read them before -- at least, words very close to them. They have appeared on the editorial page of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, where I worked for 21 years, since they were uttered in 1907 by owner Joseph Pulitzer when he retired as editor and publisher. They are affixed in hammered metal letters to the marble walls in the lobby of the Post-Dispatch building. The exact passage reads as follows:

"I know that my retirement will make no difference in its cardinal principles, that it will always fight for progress and reform, never tolerate injustice or corruption, always fight demagogues of all parties, never belong to any party, always oppose privileged classes and public plunderers, never lack sympathy with the poor, always remain devoted to the public welfare, never be satisfied with merely printing news, always be drastically independent, never be afraid to attack wrong, whether by predatory plutocracy or predatory poverty."

From 1907 to 1952 to 2010, the tools and techniques of news gathering and distribution have changed multiple times, and they'll change again. The way to gain the trust, loyalty and patronage of news consumers hasn't changed at all.

--

Eric Mink most recently was the Op-Ed editor and columnist for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. He previously covered television and media for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and the New York Daily News. He now teaches film as an adjunct assistant professor at Webster University in St. Louis.