[Bianculli here: Eric Gould, architect of this website and an actual architect to boot, was so tickled by the responses to his first post, on the applicable business improvement lessons of Gordon Ramsay, that he's written another. Go ahead and continue to spoil him. I love Eric's writing...]

(Spoiler Alert: if you haven't watched the finale, episode 14, it can still be seen online HERE.)

The seventh season of Lifetime's Project Runway just finished up, and here's another show that has a lot of rewards for artists, designers and creative types beneath the catty cloak of its reality show format. (And yes, this comes from a middle-aged, male heterosexual who is fascinated with the show. Not that there's anything wrong with that.)

Everything that gives fashion a bad name is, of course found here in abundance in Project Runway: plenty of back-stabbing, air kisses, and two-faced compliments to satisfy the reality viewer. Where else would you find more ultra-touchy feelings than in a workroom full of fashion designers? It's a perfect pattern for clashes and, um, cutting remarks.

Thankfully, that's not the total focus of Runway, which is, and always has been, one part competition, one part reality antics, and most important, one part focus on the inner creative struggle. The show starts out with sixteen contestants (including some obvious lower-level-talent fodder plants,) three of whom survive the judging to create and show a collection at Bryant Park in New York during the annual fashion week.

Contestants each week are given a new design challenge that tests their mettle. My favorite this season was episode seven, "Hard Wear," in which they were given one hour to shop in a hardware store for materials to make their next outfit. The results were surprising, ingenious creations.

Other episodes included such challenging inspirations as the circus, the four elements, designing for children, etc. -- with designers stretching to interpret a theme without being too literal about it.

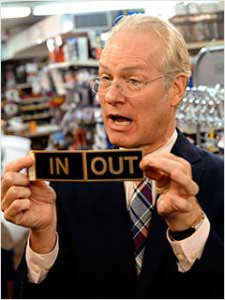

(And I wish I could, in type, phonetically characterize Tim Gunn's concerned pronunciation when he furrows his brow and says, "De-sig-ners... You have ten minutes to get your models out on the runway." Those familiar with Gunn, former chair of fashion design at Parsons School of Design and Chief Creative Officer of Liz Claiborne, will know what I mean.)

Gunn leads the contestants through the challenges, the New York fabric store Mood and the work room, while Heidi Klum, the co-host of the show, leads the judging and critiques of the work, most usually along with designer Michael Kors and Nina Garcia, Fashion Director at Marie Claire magazine.

The best parts of Project Runway are the critiques offered by Klum, Kors and Garcia about the contestants' work, especially when those contestants are backstage, out of earshot. Usually the judges' concerns are not only the quality of the clothes, but also a larger question: Is the designer capable of a full, compelling line of work? And, more important, can they grow beyond their usual comfort zone?

These were hot topics in the final episode, which saw Seth Aaron Henderson take the winning spot over a closely contested showdown with Mila Hermanovski (my pick for the winner) and Emilio Sosa. Again, it wasn't just the spark of what they saw onstage, but the depth of artist within -- their ability to leap beyond where they had been -- perhaps not embodied in the clothes they saw that day, but in the days to come.

I have to confess: These discussions are, at their heart, interchangeable with critiques found in architecture or art studios, and therein lies their fascination for me. How well is the concept translated into an actual work? Is there clarity, maturity, expertise? Is there a new take on a standard?

(Double confession: I couldn't even watch the 2008 Sundance reality show Architecture School: waaaay to close to home.)

Runway judges talk a lot about "fashion forward," eschewing simple throwbacks to other designers, decades, styles, and often demanding that designers go where they haven't before. Those in any creative field will know the cold terror behind this sort of challenge, when you can't go back to your usual, comfortable bag of tricks... even tricks you do very well.

One of the great things about this kind of critique on the show is that, even if a designer has blown a particular challenge, they are given a pass -- as Sosa was given on the "Hard Wear" episode, when he choked up a fur ball of a swimsuit made out of washers and pink cord, because the dress he had devised was too complicated and could not be finished in the allotted time. His was clearly the losing design, but another designer was voted out instead, for being deemed incapable, most likely, of going further creatively than they had already.

But, after all, this is reality television, and commercial television at that. So an hour-long discussion about why a particular angle of a cut is made, or why a certain taper or fit is chosen over another, isn't possible.

This is what Project Runway misses, and maybe could use more of: going deeper into the artistic choices the designers actually have to make, often within minutes. And exploring why they made them.

In this sense, if there were more discussion about the actual art and design of the work -- why some colors work, what different textures can convey -- perhaps there might be a deeper understanding and appreciation of the field as the real blend of art and commerce that it is.

(To be accurate, there are "Tim Gunn's Workroom" and extended judging clips on the web site, but those only emphasize the point that, on the TV series itself, they're not deemed worthy of the final cut.)

Henderson, this year's winner, in the middle of his six-month production effort for his competing line for the final event, was told by Gunn, kill-shot direct: "Although this is the excellent work we would expect from a Seth Aaron piece, I can tell you now, that if you go in this direction and present it at Bryant Park, you will lose the competition."

Henderson, this year's winner, in the middle of his six-month production effort for his competing line for the final event, was told by Gunn, kill-shot direct: "Although this is the excellent work we would expect from a Seth Aaron piece, I can tell you now, that if you go in this direction and present it at Bryant Park, you will lose the competition."

Unbelievably cold, direct, hard stuff to hear in the middle of generating work that you think is halfway finished. Henderson went on to expand and revamp the entire line, and emerged the winner of Season 7. Only by going deeper into the art -- alone with it -- was a win possible.

If we don't think fashion matters, that the art of it can't matter, think of that great moment in The Devil Wears Prada. Meryl Streep's Miranda Priestley scolds her assistant (Anne Hathaway) for her anti-fashion sense, exposing it as a pose in itself.

"You think this (the fashion world) has nothing to do with you," the editor tells her. "You go to your closet and you select out -- oh, I don't know, that lumpy blue sweater, for instance -- because you're trying to tell the world that you take yourself too seriously to care about what you put on your back.

"But what you don't know is that that sweater is not just blue, it's not turquoise, it's not lapis. It's actually cerulean. You're also blithely unaware of the fact that in 2002, Oscar De La Renta did a collection of cerulean gowns. And then I think it was Yves St Laurent, wasn't it, who showed cerulean military jackets?

"...And then cerulean quickly showed up in the collections of eight different designers. Then it filtered down through the department stores, and then trickled on down into some tragic casual corner, where you, no doubt, fished it out of some clearance bin.

"However, that blue represents millions of dollars and countless jobs, and so it's sort of comical, how you think that you've made a choice that exempts you from the fashion industry when, in fact, you're wearing the sweater that was selected for you by the people in this room."