Tap into any online news feed at any time of the day or night. Catch any television newscast or radio news summary. Scan the headlines of any newspaper. Somewhere therein, you will find evidence of human beings assaulting other human beings with such casual cruelty and violence that your brain can't even process it. Last week's mass murders in Norway offer a particularly timely illustration.

Some of these horrible events simply defy reason. Others, while every bit as damnable, can be plugged into a cause-and-effect sequence that at least seems to make them make some kind of twisted sense.

But deep at the core of every such incident lie questions that transcend the particulars: Are people fundamentally good or fundamentally evil? Are these recurring brutalities a gross distortion of the essential nature of humanity, or do they exemplify what we really are?

Philosophers and theologians will continue to argue about these things as they have for centuries. But in the meantime, a new television documentary holds out hope that humanity, in fact, may be defined by something pure and bright within us. And it finds that hope in the most improbable of settings.

Serving Life, premiering Thursday (July 28) at 9 p.m. ET on the OWN cable and satellite channel, was made in a state prison amid men who did violence or let it be done when they might have stopped it. Their choices cost them their freedom, and they are unlikely ever to be released.

The documentary shows them stripped of pretense and posturing, stripped of rationalizations for the grave consequences of their past actions. It shows them testing themselves and finding a capacity to help people who desperately need caring attention and who can offer nothing in exchange for it.

Through the acts of kindness, tenderness and self-sacrifice they perform at a bedrock human level, these men discover a sense of honor, dignity and, yes, a kind of nobility, affirming their humanity as something that is true and fine. In the process, they earn a measure of redemption by any reasonable standard of the concept.

Produced and directed by veteran journalist Lisa R. Cohen, with Forest Whitaker serving as narrator and executive producer, Serving Life documents the experiences of the volunteers and patients -- all of them prisoners -- in the hospice program at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola. The maximum-security facility houses 5100 prisoners, 86 percent of whom are violent offenders. The abundance of life sentences and the scarcity of parole possibilities decree that 85 percent of the inmates will die there.

Longtime warden Burl Cain started the hospice program in 1997. "It's just immoral not to care about somebody dying and try to have compassion when they're going to wherever they're going," Cain says.

Tending to the daily needs of people suffering from terminal illnesses is not easy or pretty work. As noted in an opening on-screen advisory, the documentary makes no attempt to sanitize these scenes or the moments of death that conclude the process. Nor should it.

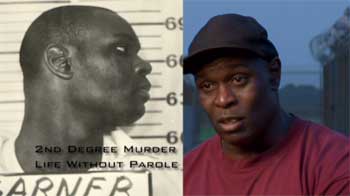

Thirty-one inmates make up the corps of hospice volunteers at Angola, but the work takes its toll, and the ranks need to be recharged from time to time. In the film, 60 people apply to join the sixth class of prison hospice caregivers, but two rounds of reviews and interviews eliminate all but eight. The film follows four of them: two armed robbers, one murderer and a drug dealer doing life via a three-strikes law.

We watch these four men -- Justin Granier, Ronald Ratliff, Charles "Boston" Rodgers and Anthony Middlebrooks Jr. (called Shaheed) -- come to grips with the physical and psychological demands of intimate personal contact with hospitalized prisoners during weeks of training. Then they begin caring for hospice patients under the watchful mentoring of experienced inmate volunteers and a small professional staff of nurses and social workers.

Some of the volunteers and patients also struggle with issues in their own lives. One of the dying patients, for example, has an older brother behind bars in another part of the prison. Their moments together -- brother with brother -- provide some of the film's most wrenching scenes.

But the heart of Serving Life is the volunteers' discovery of what it means to serve, and finding out if they are capable of it. Sometimes, the challenge is raw and physical: cleaning patients' soiled bodies of urine and feces. More often, service is a volunteer keeping watch at bedside while a patient he has come to know and care for slips through his last few hours of life. The caregiver holds a hand, strokes a forehead, applies lotion to drying skin, whispers comforting assurances to someone who probably can't hear them, just in case.

"Early in my career here," Warden Cain says, "I started to realize the only true rehabilitation was moral. I can teach you skills and trades, but I'd just make a smarter criminal unless we get something in our heart, unless we become moral.... A criminal is a selfish person. Whatever he wants, he takes it. So the way to be the opposite of that taker is to be the giver. The ultimate gift is to be the hospice caregiver."

There are a couple of moments when Serving Life seems to doubt itself and calls on production devices to artificially inflate its considerable emotional impact: a musical score that becomes needlessly intrusive, a slow-motion montage that feels hokey.

But these are minor glitches compared to the documentary's astute use of moving images and sound to tell stories of extraordinary poignance. What this filmmaking artistry reveals is imprisoned men with backgrounds of violence and no hope of release finding the strength to sacrifice and the morality of giving for its own sake. In embracing these values, the men reveal the vital core of their humanity and, by extension, of ours: simple goodness and a beauty of spirit that can retain the power to redeem.

--

Eric Mink -- ericmink1@gmail.com -- most recently was the Op-Ed editor and columnist for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. He previously covered television and media for the Post-Dispatch and the New York Daily News. Mink teaches film studies at Webster University in St. Louis and provides writing and editing services to independent clients.