[

Bianculli here: Contributing critic Eric Mink has weighed in with a wonderful piece on Daniel Schorr, who died Friday. Here it is:]

There's a great Yiddish word for Dan Schorr:

noodge.

Either a noun or a verb depending on context, the word describes both a kind of conduct and the kind of person who engages in the conduct. The most apt definition I found for "to noodge" is "to annoy with persistent complaining, asking, urging, etc." You can quibble about style, but I'd argue that great reporters have a lot of noodge in them.

Schorr was a noodge of the highest order.

Early in his career, Schorr's reporting annoyed President Dwight D. Eisenhower, irritated President John F. Kennedy and got him kicked out of the Soviet Union by Premier Nikita Khruschev. Schorr was such a noodge questioning East German Communist dictator Walter Ulbricht that Ulbricht broke off the interview and stormed out of the room, leaving Schorr facing an empty chair.

Much later in his career, Schorr took a stand on principle that vexed and perplexed Ted Turner, the television visionary who had hired Schorr in 1979 to be the first employee of what was to become the nation's first 24-hour news channel: CNN.

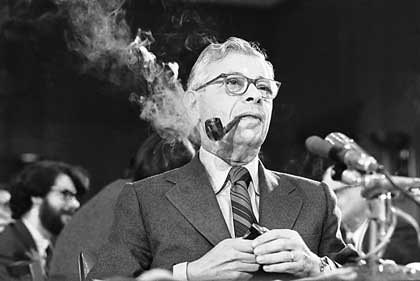

But newsman Daniel Schorr, who died July 23 at age 93, really got to U.S. President Richard M. Nixon. And Nixon's inability to manage his anger helped bring down his presidency.

In 1971, Nixon sicced the FBI and the IRS on Schorr after he broadcast reports for CBS News on Nixon's failure to fulfill a pledge to assist Catholic schools.

"You take a fellow like this Dan Schorr," Nixon complained on Sept. 18, 1971, to chief of staff H.R. Haldeman in a tape recorded Oval Office conversation transcribed by the University of Virginia. "He is always creating something, isn't he?"

Haldeman replied, "You don't, shouldn't get involved in this, but he's on our tax list, too."

"Good," Nixon said. "Pound these people."

Later in the conversation, Nixon and Haldeman discussed a trumped-up FBI investigation of Schorr and prepared a phony cover story about Schorr being considered for a federal appointment.

The second article of impeachment adopted by the House Committee on the Judiciary on July 27, 1974, charged Nixon with abusing his authority over government agencies by targeting certain U.S. citizens for illegal investigations. Schorr was one of those cited in the record. Thirteen days later, Nixon slinked off into history as the only American president ever to resign from office.

In a piece about Schorr for The Nation last week, John Nicholswrote that "Schorr's unofficial beat was always the abuse ofpower," which gets it just right.

In a piece about Schorr for The Nation last week, John Nicholswrote that "Schorr's unofficial beat was always the abuse ofpower," which gets it just right.

But on one glaring occasion, Schorr's single-minded, hard-headed dedication to that mission brought him grief not only from the powerful but also from some of his own colleagues.

In the summer of 1975, Schorr was on the intelligence beat for CBS News, pursuing stories of abuses by the CIA, FBI and other agencies. Simultaneous investigations by special committees in the House and Senate were uncovering a long and sordid record of illegal activity at home and abroad.

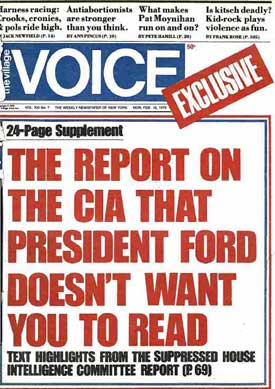

The House committee, chaired by New York Democrat Otis Pike, completed its investigation and voted to publish its findings with sensitive national security information deleted. But under pressure from then-President Gerald Ford, the full House voted to keep even the edited version of the committee's report secret.

Schorr got a copy of the report from a trusted source and began filing on-air reports about its contents. But CBS executives would not agree to supplement its broadcast reporting with print publication of the complete document. Without CBS' approval or knowledge -- and fearing that the full report might never see the light of day -- Schorr secretly gave the report to the Village Voice. The Voice published it on Feb. 16, 1976, as a 24-page supplement with the front-page headline, "The report on the CIA that President Ford doesn't want you to read."

It was a bombshell, and CBS executives were not happy.

Schorr recounted the aftermath in a 90th-birthday interview with NPR's Robert Siegel in 2006. The day the Voice hit the stands, Schorr said he was called into the office of Sanford Socolow, then the Washington bureau chief of CBS News, and asked what he knew about the Voice's publication. Schorr said he ducked the question.

Then, according to Schorr, Socolow noted that Lesley Stahl, then a CBS White House reporter, was dating Aaron Latham, a writer for New York magazine. New York magazine and the Village Voice were both owned by editor/publisher Clay Felker. Socolow asked Schorr if he thought there might be a connection between Stahl's romantic relationship and the Voice's publication of the Pike report.

As Schorr described it on NPR, "I said, 'Ummm. Who knows?' I allowed him to entertain that thought for one day. The next day ... I went into Sandy Socolow's office and said, 'Forget what I said yesterday. Stop looking for who it was.'"

Stahl's account is radically different. In Reporting Live, the memoir she published in 2000, Stahl quotes by name CBS News executives who said Schorr told them he believed Stahl had taken the report from his desk and leaked it to the Voice. She points out that the Washington Post identified Schorr as the leaker before Schorr says he told Socolow. And she says that Socolow called Schorr a liar.

The House ethics committee investigated the leak and called Schorr to testify. He refused to say who gave him the report, and the committee eventually declined to cite Schorr for contempt.

With the legal situation resolved, Schorr sat for a 60 Minutes interview with Mike Wallace in which he denied implicating Stahl. The next day he resigned from CBS, and according to Stahl, she got his office. Her memoir describes a phone call from Schorr several weeks later as a half-hearted and not very convincing apology.

Twenty years later, the rift was still raw.

On January 25, 1996, I sat in the front row at Low Library on the campus of Columbia University as Schorr accepted the duPont-Columbia Gold Baton for "exceptional lifetime contributions to radio and television reporting and commentary." I was a member of the seven-person jury that had given Schorr the Gold Baton, awarded only in those years when we believed there was a worthy candidate.

Schorr's official National Public Radio biography, which Schorr undoubtedly reviewed and approved, gives the Gold Baton the greatest prominence among his many awards, saying "[it] is the most prestigious award in the field of broadcasting and is considered the equivalent of the Pulitzer Prize."

The host of the awards that year was Ted Koppel, then the anchor and managing editor of ABC News' Nightline.

As the ceremonies drew near, I thought Schorr's award would have special resonance that night, considering that at least two of the Silver Baton honors that year were going to programs on issues Schorr had covered himself with distinction: The Discovery Channel's Watergate, a five-hour documentary (also narrated by Schorr); and PBS' America's War on Poverty, a five-hour documentary by Blackside Productions, and a story Schorr had covered when he returned from his European posting for CBS in the mid-1960s.

In accordance with long-standing tradition, Columbia's president at the time, George Rupp, would present the Gold Baton. The scheduled Silver Baton presenters had been announced a month earlier: Koppel of ABC; Schorr, by then 11 years into his 25-year run at NPR; Tim Russert of NBC; Ralph Begleiter of CNN' PBS's Charlie Rose; and, representing CBS News, Lesley Stahl.

On January 24, one day before the awards ceremony, Stahl cancelled.

--

Eric Mink most recently was the Op-Ed editor and columnist for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. He previously covered television and media for the St Louis Post-Dispatch and the New York Daily News. He now teaches film as an adjunct assistant professor at Webster University in St. Louis.