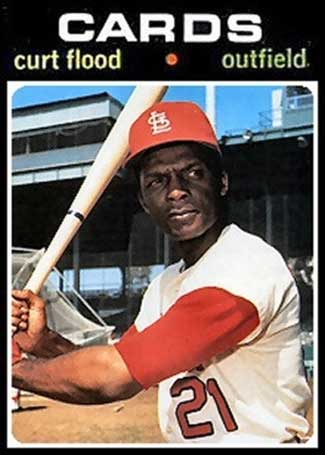

Curt Flood started in center field for the St. Louis Cardinals of my childhood and adolescence. He was an alcoholic. He abandoned his family. He ran away from a team in the middle of a season and never came back. He welched on debts and didn't pay his taxes. He operated a side business that conned fans out of thousands of dollars. He helped the Cardinals win World Series titles in 1964 and 1967, but in the '68 Series, he missed a fly ball in the seventh inning of the seventh game that arguably made the Detroit Tigers that year's champions.

Curt Flood is one of my heroes...

Irresponsible, dishonorable and self-destructive behavior is not the stuff of which heroes are made, yet Flood's heroism was genuine and true, not only to me but also to countless other fans and, perhaps most especially, to all professional athletes who have come since, and who owe him a debt that is beyond repayment.

How these contradictions co-existed in the person and life of Curt Flood is the animating spirit of a new documentary premiering Wednesday night [July 13] at 9 p.m. ET on HBO.

The Curious Case of Curt Flood lays out the triumphant and tragic dimensions of Flood's baseball career and personal life. Its principal narrative thread is the quixotic legal battle Flood waged with the baseball establishment at the peak of his career.

In the fall of 1969, the Cardinals decided to trade Flood and catcher Tim McCarver to the Philadelphia Phillies for slugging outfielder Dick Allen. Flood decided to say no. Player contracts didn't give him the right to say no, but Flood declared he would not allow himself to be treated as if he were someone else's property, no matter how well paid he was.

On January 16, 1970, two days before his 32nd birthday and after intense consultations with the lawyers leading the players' union at the time, Flood filed a federal lawsuit against the most powerful people in Major League Baseball: the team owners, the commissioner, and the presidents of the two leagues. Contract clauses notwithstanding, Flood argued, baseball had neither the legal right nor the moral right to deny any player a say in where and for whom he would work.

As the case crept through the federal court system, Flood's personal life crumbled. He was bombarded by hate mail, death threats and savage racial insults. He was effectively abandoned by former teammates. Relationships dissolved. His money dried up. He drank constantly. He signed with baseball's worst team, the Washington Senators, but his skills had eroded and he quit the team -- by telegram -- never to play again. Then he fled to Denmark without telling anyone where he was going or where he was once he got there.

In the summer of 1972, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against Flood, 5-to-3. In its majority opinion, the Court admitted that baseball did not merit special treatment under the law, but it refused to reverse two previous decisions granting it that special treatment.

Flood's downward spiral accelerated. Even three years later, when players' union collective bargaining efforts (energized in large part by Flood's unsuccessful lawsuit) freed players from the absolute control of team owners, Flood was too deep in alcoholism, depression and despair to appreciate it. Not that players seemed inclined to credit him.

In The Curious Case of Curt Flood, interviews with family members, friends, teammates, professional associates and adversaries, journalists and authors attest to the private agonies that accompanied Flood's all-too-public struggles.

Producer Ezra Edelman and his HBO Sports team keep the screen alive with archival news footage, official and personal photos, game highlights, close-ups of newspaper pages and artful isolations of key passages in legal documents. Flood speaks for himself over the course of some 30 years, in news clips and interviews with the likes of Howard Cosell, Roy Firestone and "Easy" Ed Macauley, a St. Louis college and pro basketball star turned local sportscaster.

This is an extremely tough and unflinching film. It is as sharp and direct in addressing Flood's flaws as it is forthright in celebrating his undeniable athletic skills: a consistently productive hitter (.293 batting average over 15 seasons) and a fielder of extraordinary speed and range (seven straight Gold Glove awards from 1963 through 1969).

Yet relentless honesty -- uncommon as it is in film biographies, sports biographies especially -- is not this film's most remarkable achievement. That distinction belongs to Edelman's success in resolving the seemingly irreconcilable differences between Flood's conduct and our knee-jerk notions of heroism.

The film carefully lays a foundation for this point of view: First, Flood did not stumble into an against-all-odds conflict; he knew precisely what he was getting into. Players' union lawyers counseled him at length that success was unlikely in light of existing Supreme Court precedents. He also understood that even if he prevailed, it would take so long that he would not benefit personally. A victory would be a victory for other current players and for future players, but not for him. Neither point dissuaded Flood from proceeding.

Finally, Flood's character flaws and failings made him an ordinary person in an extraordinary situation. Even Flood's closest friends did not dream he was someone who would get into a fight to the finish with the system. But in real life, heroes are not perfect people who act heroically simply because that's what perfect people do. Flood, a distinctly imperfect man, discovered a reservoir of inner courage that allowed him to risk his personal security and well being for the benefit of others.

After years of self-loathing and life-threatening alcohol abuse, Flood began to find a measure of redemption. He reconnected with a girlfriend he had abandoned decades earlier, actress Judy Pace (right), who encouraged and insisted on his return to sobriety and supported him as he worked on it. They later married, and Judy Pace Flood is credited as a consultant to the HBO documentary. Flood also rebuilt his ravaged relationships with the now-grown children of his first marriage.

But it wasn't until 1994, in the midst of a strike against team owners, that a new generation of major league players gave Flood the acknowledgment and appreciation they owed him for his sacrifice on their behalf.

The Curious Case of Curt Flood is unsparing, but it is not unkind. Curt Flood was a troubled man with a need gnawing inside him. But a need for what: Love? Respect? A place in history? A need to stand up to injustice? To change baseball? To help players? To improve the status of African Americans, as one of his heroes, Jackie Robinson, had done? Probably bits of all those things.

But ultimately he was a flawed human being who was neither thoroughly admirable nor thoroughly deplorable. Just like the rest of us. Except that when his moment came, he acted heroically. Not like very many of us at all.

--

Eric Mink -- ericmink1@gmail.com -- most recently was the Op-Ed editor and columnist for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. He previously covered television and media for the Post-Dispatch and the New York Daily News. Mink teaches film studies at Webster University in St. Louis and provides writing and editing services to independent clients.