One of the very first images in director Martin Scorsese's fab four-hour HBO documentary biography, George Harrison: Living in the Material World, shows the former Beatle playing hide-and-seek with the camera, partly obscured by a bunch of colorful tulips.

By the next time we see that same image, near the end of the two-part program, it's saturated not only with color, but with meaning...

By then, we know so much about "the quiet Beatle," including the fact that he painstakingly and constantly returned to his own garden, finding peace and happiness in toiling with his own hands, and seeking to craft and nurture small patches of transient, but inspirational, beauty.

Scorsese is the type of filmmaker, whether dealing with fiction or nonfiction, who embraces symbolism like a poet -- or a lyricist. So when he plants Harrison in the same garden as the late musician's beloved flowers, the meaning, especially the second time around, seems clear, and applied equally to the tulips and to Harrison:

What a temporary but breathtaking thing of beauty.

George Harrison: Living in the Material World premieres Wednesday and Thursday, Oct. 5-6, at 9 p.m. ET on HBO. Watch and record both parts, because you'll want to revisit and review these often. Scorsese's last two-part TV documentary about a musician, 2005's Bob Dylan: No Direction Home, was an American Masters masterpiece for PBS. This one, on Harrison, is just as good -- and, afterward, even more haunting.

What's most impressive about this new study is that, even after ABC's exhaustive Beatles Anthology documentary miniseries in 1995, there's so much original material and formerly unseen footage here. Part of it, it turns out, is due to Harrison's wariness, while cooperating with the other surviving Beatles on that program, that he was in danger of again getting short shrift, just as he had when songs were parceled out on the various Beatle LPs in the 1960s.

So he began filming himself, from time to time, and stockpiling interviews telling his own story and stories, just in case. Harrison died in 2001, after battling both cancer and an intruder who invaded his home and stabbed him repeatedly and seriously. So his widow, Olivia Harrison, released those materials and others to Scorsese, and, along with son Dhani, sat for new interviews. She, along with Scorsese and Nigel Sinclair, is one of the producers of Material World, but she does no whitewashing of her husband's legacy.

In fact, one of the funniest moments in the entire documentary comes when Olivia, after being candid about Harrison's occasional marital meanderings, asks and answers her own tough question.

"What's the secret of a long marriage?" she asks

Then she adds, with a wry smile: "You don't get divorced."

But there's lots and lots of true love on display here. Another standout moment, among many in Material World, comes when George is shown fiddling around with teenage son Dhani, playing guitar, in a recording-studio control room. At one point, they hug -- a father-son moment that Dhani is fortunate enough to have frozen in time, at least on film.

I'm a major Beatles fan, so the majority of material in this four hours was familiar to me -- but some was new, and Harrison's story is told, impressively and almost amazingly, without relying too much on the Beatles part of it.

Harrison's life journey, like his spiritual journey, took its own course. The musician who introduced the sitar to most American ears on "Norwegian Wood" was fond, and unafraid, of paving his own path: to Indian music and Eastern religion, and to follow his enthusiasms and make life-long friends of race car drivers, comedians and lots of others.

Harrison's story also includes Monty Python (he financed their first big film), Eric Clapton (who wrote "Layla" as a successful attempt to woo Harrison's then-wife, Pattie, away from him), Bob Dylan (and the other Traveling Wilburys), and so many, many more.

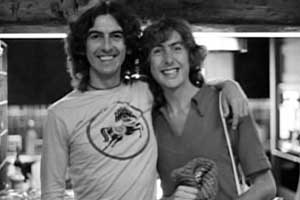

Interviewed for this documentary are some key players -- Ringo Starr gets tearful, while Paul McCartney faithfully keeps some bad-boy secrets private. But others important to Harrison's story are here, too, including first wife Pattie Boyd, early German friends Astrid Kirchher and Klaus Voorman, Eric Idle (seen here with Harrison), Terry Gilliam, producer Phil Spector (!), as well as Clapton, Tom Petty, Billy Preston, Ravi Shankar and other musicians who recorded with, and were befriended by, Harrison.

Part 1 of Material World, shown Wednesday, takes us through the Beatles era -- from the heady, giddy days of Liverpool and Germany, when Harrison was the group's raw but talented underage lead guitarist, to the dour days recording Let it Be as both an album and a movie. Harrison and McCartney are shown in a scene from that movie, arguing testily though quietly about what sort of guitar part McCartney wanted Harrison to provide.

Part 2, shown Thursday, moves on to the concert for Bangladesh, the first rock charity concert (and still one of the best filmed rock concerts of all time; buy it HERE); to Harrison's close alliance with the Pythons, which started when he mortgaged his mansion to fund the launch of Handmade Films and Monty Python's Life of Brian; to Harrison's successful solo career; and his late-era comeback with Dylan, Petty, Roy Orbison and Jeff Lynne in the Wilburys.

The nuggets to be discovered here are so choice, I'll leave most of them buried for viewers to find on their own. But I can't resist naming two. I didn't know, for example, that Harrison's "Let Me In" was written about Dylan, as an appeal to an old friend to be less remote. And Petty reveals what Harrison said just after Orbison died -- a shockingly honest thing to say, as well as to reveal.

Near the end of the show, when Olivia recounts the home invasion in which she and her husband fought off a crazed intruder, things get emotional as well as intimate. It happens again when Ringo, recalling his last moment with George, wells up with tears. Or, if you prefer, gently weeps.

"God, it's like 'Barbara f***ing Walters' here, isn't it?" he asks.

No, it's a lot better than that.

George Harrison: Living in the Material World ends with a chant, sung by Harrison, that is gorgeous, and hovers in the ear, and the mind, long after the documentary is over.

Much of Scorsese's loving character study is like that. It's a pleasure to watch, and to hear -- and, afterward, just as pleasant to ponder.