Jesse Owens’ life was the stuff of which dreams are made, in spite of the nightmarish detours he took because of the virulent racism of the early 20th century. He was an American hero. He was a slightly flawed hero whose record-setting exploits in track took him to the 1936 Olympics, yet still did not shield him from racism. He girded himself to face the racism of 1936 Berlin, but was struck numb by how quickly an America who celebrated him in Germany turned and treated him as an inferior shortly after his return home.

His family was part of the Great Migration of African Americans who left the Jim Crow South in search of freedom and opportunity in the industrial North. They found a portion of that elusive freedom in Cleveland, where Owens excelled in track from his discovery in junior high school through his record-breaking performances at Ohio State University.

Still, those who know of Jesse Owens see his life almost exclusively through his four-gold-medal performance in the 1936 Olympics, where Adolf Hitler was poised to show the world the supremacy of the Aryan race. Owens punctured that myth with track spikes that in four days left Hitler angry and Germans in awe of the African American’s athletic prowess. The well-documented 1936 Games get a very well done retelling in

Jesse Owens, as part of the PBS series

American Experience, premiering Tuesday, May 1 at 8 p.m. ET.

This documentary presents an amazing sweep of skillful reporting and storytelling that not only plumbs exquisite film archives, but takes pains to find Germans who attended the Berlin Olympics. And their recollections are fascinating because they reveal the wide-eyed memories of children who saw brilliant competition through the gauze of the overwhelming Nazi propaganda that covered the Games.

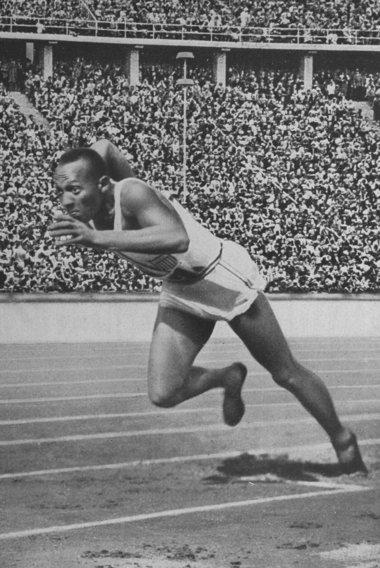

The film also is beautiful to watch. The historic footage, despite much of it having been seen in other stories about Owens and the '36 Olympics, is fascinating on its own. But the historic footage is enhanced by brilliant photographs of an immensely athletic Owens who just seemed to be built for speed and destined for stardom. His muscles seemed perfect for world-record sprints. His handsome visage was camera ready. When flashed in a slow-motion sequence of photographs across the documentary screen, Owens appeared to be chiseled on Mt. Olympus.

But, as all gods, Owens had a few flaws and this documentary was honest enough to speak of them without criticism or judgment. On his West Coast swing to compete in the National Collegiate Athletic Association track championships, Owens was dazzled by Hollywood and the life led by prosperous African Americans out West. Owens enjoyed himself and his keeping company with a woman in Los Angeles publicly raised questions about his faithfulness to his girlfriend and child in Ohio.

The upshot was an athlete whose competitive interest waned, whose training suffered and who ran into a Temple University runner who beat Owens handily over several occasions. That fall from athletic grace prompted Owens to go home, marry his girlfriend and return to the seriousness of his training to prepare for the Olympics.

The setting in Berlin, of course, was just too delicious to ignore: The Nazi propaganda machine offering the grandest stage possible to demonstrate Aryan supremacy and U.S. hopes resting on the shoulders of the progeny of an enslaved race. It was a kind of pride that even today beams in the expression of Louis Stokes. The documentary identifies Stokes as a Cleveland resident, but overlooks the fact that Stokes served 30 years in the United States Congress. (His brother, Carl Stokes, was the first African American elected mayor of Cleveland.)

The documentary has several historic threads that might have been left hanging by the necessity of time. For example, Ralph Metcalfe, who also was African American, finished second to Owens in the 100 at Berlin and went on to be president of the Chicago City Council. In a way, they helped lay the foundation for Jack Roosevelt Robinson to integrate Major League Baseball in 1947.

Overall, though, the documentary doesn’t disappoint. Owens’ role in the Olympics gets a rich retelling. Quotes from Hitler and passages from Joseph Goebbels’ diary tell the story. Although many might recall Hitler’s snubbing Owens after he won the 100-yard dash, few might be fully aware of just how Owens’ brilliant performance captivated the German crowd.

Some of that may have been fueled by his intense battle with Carl Ludwig "Luz" Long for a gold medal in the long jump. The documentary lets the competition unfold like a heavyweight fight, with Long doing two things though that stood as acts of pure sportsmanship. He offered Owens a tip that helped him succeed at his third and final qualifying jump, and Long embraced Owens then trotted arm-in-arm with him after the lengthy battle that Owens won with a leap of 26 feet.

Interviews bring some absolutely precious detail to the documentary, and if offered as an interview reel alone, Jesse Owens would be well worth watching. The outstanding reporting and interspersed historic data, coupled with stellar visuals, however, complete this excellent story.