BEVERLY HILLS, Calif. — When it's time for another multi-hour examination of American history or culture from Ken Burns (top), it's usually the articulate director who spends the most time talking during press events.

At an extended session for his upcoming 16-hour Country Music at the TV Critics Association summer press tour, though, Burns took a back seat to the explication of the country stars and film subjects he got on the panel — an especially expressive and expansive Dwight Yoakam (below), Rosanne Cash (top), and Marty Stuart (top).

It was Yoakam, after all, who stops the film in its third chapter by recalling from memory the stark lyrics of a 1974 Merle Haggard B-side, "Holding Things Together" and then having to pause, choking up at the emotion of its plain and human words.

It was Yoakam, after all, who stops the film in its third chapter by recalling from memory the stark lyrics of a 1974 Merle Haggard B-side, "Holding Things Together" and then having to pause, choking up at the emotion of its plain and human words.

Burns says he always wanted his films to have what he calls "emotional archeology" — something he describes not as sentimentality or nostalgia but something "that would seek what we all look for in our lives, something higher than the mundane, where periodically one and one equals three and not two."

And Country Music ended up having that in spades.

"We were unprepared for the kind of higher emotions we would run into and find unavoidable in mastering this very complicated story about this music," Burns says.

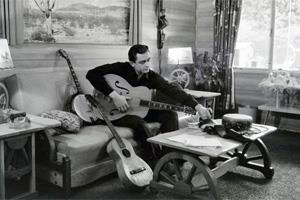

It came in part from presenting the well- and lesser-known names from the field, from the Maddox Brothers and Rose and Ralph Stanley to household heroes like Johnny Cash (bottom), Buck Owens, and Haggard, of whom Yoakam surmised, "you could argue that between '67 and '72, there's no greater American musical poet maybe than Merle Haggard."

Yoakam says he knew Owens and Johnny Cash as a kid but didn't get to know Haggard until he was a young man, "because he sang about adult issues."

Outsiders and working people were all derisively called Okies, though Haggard (left) "was born in the labor camp here in California."

Outsiders and working people were all derisively called Okies, though Haggard (left) "was born in the labor camp here in California."

"Merle's able to talk about that in a wildly literal way," he says. " 'Mama's Hungry Eyes' is an example of that. That song is as elegant a piece of writing as Steinbeck."

"He was called the poet of the common man, and it's really true," Burns says. "I think Dwight and many people in the film, but particularly Dwight, helped understand who he was."

Burns says they were fortunate to have interviewed Haggard before he died in 2016 at 79. "He is in almost every episode, and I've referred to him as Zeus every time he speaks. It's like a thunderbolt coming down."

Yoakam is one of a variety of thoughtful country singers who give their knowledge of the history of the genre, so much so that they needn't have contacted musicologists.

"Usually, we have quite a few historians helping us help guide the narrative," producer Julie Dunfey says. "What we discovered when we started doing our interviews is that so many of the artists, musicians, producers were historians of their work. They know where they came from. They knew the songs, they knew the traditions. And we found out we only have one historian in the film."

Cash says she learned more about her storied family history than she knew before.

Cash says she learned more about her storied family history than she knew before.

"I feel so tremendously honored [with] the respect my family was given in this film, and I feel proud of it," she says. "In my early career, I spent so much time trying to wrest myself from out of my dad's shadow, and I probably pushed away longer than was gracious — not from him personally, but from my own legacy and the own tradition I came from. Luckily, I got wise about that and accepted it. But this has given me another level of being empowered about my own tradition."

Stuart, who got into traditional music early with a stint with Flatt and Scruggs as a 13-year-old (above, with Lester Flatt), and later married the country star on whom he had a childhood crush, Connie Smith, provided a trove of materials he's collected over the years.

Flying directly from the East Coast where he was touring with his band The Fabulous Superlatives, Stuart was effusive about the Burns series.

"I think it gives the traditional country fan, who never thought they would hear or see this again, a sense of victory," he says. "I think it also gives people who have really never given country music much regard other than the face value of it, here's your chance to get inside of it to see what a beautiful culture it is, and something in there will pertain to your life."

Finally, he adds, "I think a lot of the artists that are playing country music, the current stars, they probably haven't had the same kind of upbringing that Dwight and Rosanne and myself have had. I think it gives the opportunity to look inside of this culture and go deep."

Cash says she knows how deep a country song can connect with an audience. One of her songs she mentioned, "House on the Lake," was so personal to her, with such specific details, she was hesitant to do it live.

Cash says she knows how deep a country song can connect with an audience. One of her songs she mentioned, "House on the Lake," was so personal to her, with such specific details, she was hesitant to do it live.

"The first time I performed it, I was really nervous," she says. "And when I came off stage, this guy came up to me, and he says, 'Everybody has got their house on the lake.'

"And it clicked for me that no matter how personal it was to me, that they were bringing their own lives [to the songs], and they heard these songs through the prism of their own lives. And that is community, and that is healing for people to recognize their own stories in something in art," she said. "That's the function. We are in the premier service industry of the heart and soul. That's what artists do."

Country Music premieres on PBS Sept. 15, one week after a special Country Music: Live at the Ryan, a Concert Celebrating the Film by Ken Burns Sept. 8 (check local listings).