By History Channel standards, The Men Who Built America is a lavish production. How it interprets the lives of its central figures — railroad baron Cornelius Vanderbilt and oilman John D. Rockefeller in the first two episodes — is akin to a long infomercial for the current Republican Party.

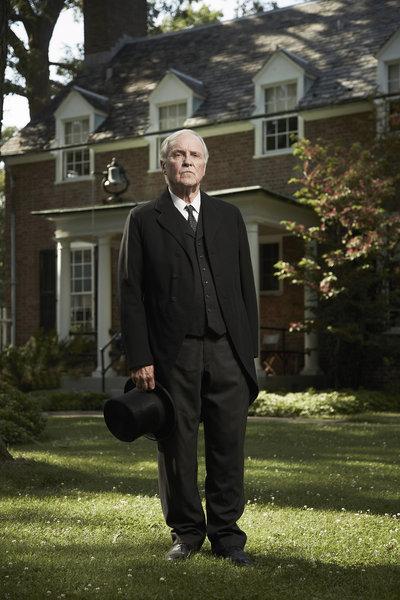

Railroad buffs will revel in the footage of Gilded Age locomotives chugging across verdant landscapes. Where there are humans, there is historical reenactment. These humans —a grey-bearded “Vanderbilt” solemnly puffing his cigar, a chisel-jawed actor playing a young Rockefeller — say little. Unless, that is, they are negotiating a multi-million-dollar deal in a few terse lines: “I will ruin you,” that sort of thing.

Rather, the series, which premieres Tuesday, Oct. 16 at 9 p.m. ET, is heavily narrated, front to back. The reenacted scenes are shot in a kind of sepia-tone warmth, with period costumes, mansions, grungy street scenes and oil derricks enough to delight any History Channel fan who’s had his fill of Nazis, Nazis, and more Nazis. Come to think of it, most HC fans probably can never get enough Hitler. But this series is likely to attract other audiences because Americans seem to never tire of the exploits of our “captains of industry” or “robber barons.” The problem with this series is that it never poses or even hints at this very intriguing question: Which were they?

The strong editorial stance of the series is broadcast the loudest by its talking heads. There are, to be sure, a couple of historians, such as T.J. Stiles, because of his recent table-sagging biography of “The Commodore” Vanderbilt.

The show’s producers made an important strategic decision. They chose several of today’s top business men (plus Alan Greenspan), including Mark Cuban, Donald Trump, Jack Welch and Ted Turner to speak on behalf of their progenitors. On camera these men are unalloyed boosters for hypercapitalism. They seem almost wistful that they couldn’t be transported back to an era before federal regulation, an era of, as one describes it inaccurately, “pure competition.” They only see the brains and drive at the very top; all the rest is invisible.

Even downright dastardly acts are reported but not questioned. When Jim Fiske and Jay Gould “water” shares of stock by running off hundreds of essentially bogus stock certificates, the practice is deemed a “brilliant innovation.” Shaky derivatives, anyone?

Without foraging too deeply into the weeds of business tactics, the series mostly gets the big strategic decisions right: Vanderbilt’s diversification from shipping into railroads, Rockefeller’s focus on refining instead of drilling, the importance of controlling Cleveland-area shipping and refining.

But there are some major missteps, as when, in a long segment, we see the Rockefeller character, locked in battle against the railroads, staring at pipes of various sorts until — voila — he dreams up the idea of the oil pipeline! Yet as Daniel Yergin writes in his magisterial history of oil, The Prize (1991), "Pennsylvania [oil] producers made one effort to break out of Standard's suffocating embrace with a daring experiment — the world's first attempt at a long-distance pipeline. There was no precedent for the project..." In other words, Rockefeller’s competitors invented the pipeline to break his stranglehold on markets.

To carry the show with a core, dramatic narrative, The Men Who Built America conveys the impression that the economy was virtually completely controlled by a half dozen men. Did Rockefeller’s life really change when old man Vanderbilt finally met his maker? What about all the other railroad leaders and oil producers and even middle-sized firms he had to deal with?

Years ago a team of labor historians published a two-volume study called Who Built America? It’s a good question. In The Men Who Built America, workers are invisible, except when laying pipelines or rioting. Competitors are largely invisible, except when beaten. Millions of ordinary citizens, worried that these men posed a fundamental threat to American democracy and economic opportunity, are invisible. Journalists who filled newspapers with muckraking stories and political cartoons about the “robber barons” are invisible. Yet Rockefeller deserves his Ida Tarbell (who relentlessly attacked him in print), just as Sherlock Holmes deserves his Professor Moriarty.

The power these few men exercised was unprecedented. Everything they did was not good for the U.S. economy. Isn’t that a more interesting way of looking at their careers?