The internet was rife last week with postmortems on the season finales of AMC's Mad Men and Rubicon. And with good reason: These two shows gave us the most to discuss simply because they were better -- and smarter -- than everything else TV had to offer.

No other shows (save HBO's Boardwalk Empire and a few other precious contenders) boasted the compelling writing, directing, acting and art direction that kept us not only coming back week after week, but discussing it all six days in between.

With Breaking Bad and Mad Men already in their arsenal, and this year with Rubicon and the upcoming The Walking Dead (which I've seen in advance), AMC has qualitatively knocked HBO from its long-time Sunday night pedestal, when that night used to be dominated, in terms of quality TV, by HBO.

At the same time, AMC shows are the clear losers quantitatively, with the ratings showing Mad Men losing to Keeping Up With the Kardashians in the same time slot, and Rubicon falling behind Swamp People by almost half in their same-hour competition.

Of course, we shouldn't be surprised by those losses, or discouraged by them. One has to presume AMC is profiting from small audiences (or at least not hemorrhaging because of them), and is getting wide critical acclaim from almost every corner. We'll find out soon enough if they have the stones to re-up Rubicon, which at times suffered from what some (but not I) saw as a lethargic pace and an underwhelming audience body count.

But the real winners here are we viewers: Audiences in search of smart, stylish, dramas that made us think, and then consider more deeply, the complexities and themes we were given each week.

Not that there weren't flaws.

With Mad Men, we were asked at the beginning of the season, "Who is Don Draper?," only to find out by season's end that he was neither simply DIck Whitman nor Don Draper, but perhaps a complex blend of the two -- suddenly topped with a whipped cream dollop of a love-struck schoolgirl skipping off to a hasty engagement in a business suit.

Throwing caution to the wind on a family trip to Disneyland (of course,) he asks his secretary Megan to marry him after a micro-dating period, and fobbing off Faye, the one mature, self-integrated figure he's encountered who has accepted him as he is, completely, without judgment.

It felt eerily like a writer's flea-flicker trick play, with Don so out of character, and perhaps the first sign of shark-jumping that Mad Men may be running out steam.

So be it. Every series faces the moment where new plot lines and characters feel contrived. Mad Men will not be immune to the problem of a great show wondering where to go. The Sopranos managed to avoid it by coming back every other year, and also maintaining longevity through small, quirky shifts in tone that didn't stretch credibility too far, but gave characters fresh environments in which to work. It was an amazing fine line that David Chase designed for himself to walk.

I'll keep watching Mad Men not so much for the various dramatic plot threads, but more for an examination and understanding of the enormous cultural upheavals of the '60s and early '70s that are in store for its characters. Mad Men looks at a the mid-twentieth century so well: a stylish, colorful spree of modernism and hair products that gloss over very troubling and repressive post-war social roles, which the characters are finding out, in various ways, do not suit them all that well. Much of the drama in Mad Men is men and women acting out against roles they've come to realize are life-long binds.

It's what happened to all of us of that era, and it was a time when society as a whole threw off the safe, mass-manufactured conventions of the Eisenhower years -- the ranch house and Ozzie and Harriet. En masse, we went into psychotherapy to examine whether life was just the pursuit of a mortgage and a color TV, or if there weren't something more to the whole thing.

The family unit as the cultural foundation was beginning to fracture, and along with it, the feelings of certainty that once lay ahead. We consciously traded that security for something unknown -- a high-wire act we're still performing. Where it lands, nobody knows, but Mad Men helps us take a piercing look at how we got here.

Rubicon persists in my brain like the speech affectation of Truxton Spangler (Michael Cristofer), his quirky accent perched somewhere between Sir John Gielgud and Stanley Kowalski. It challenged other conventions as well, most significantly with its narrative conceit -- namely, that a story could be told in slowly peeling layers, quietly.

It's a show that will perhaps come to be recognized as the spy-thriller giving us exactly one on-camera gun shot fired during the entire season. (Which is precisely one more than any of us will hear during a life time, and also the equivalent number found every two seconds during an episode of the new Hawaii Five-O.)

It took a hard look, in the alienating style of the film Three Days of the Condor, at Eisenhower's warning that the military-industrial complex would be driving the bus, instead of protecting it. Rubicon revealed some very powerful corporations and men inside the government, prodding along terrorist events to their own financial and political gain, with precious little patriotism to be found.

Rubicon asked that we seriously look at political conflicts conducted silently in the background through the might of information superiority, the manipulation of mass-media, the culture of fear, proxy wars and client states... all through the beleaguered eyes of Will Travers (James Badge Dale) and the others at the fictional American Policy Institute, a counter-intelligence group of analysts higher up than the CIA or NSA.

Not that the show didn't have loose ends and odd plot threads. (I would be committing a grievous reportage failure if I did not acknowledge, and steer you to, Andy Greenwald's hilarious unmasking of various loopholes in the season finale in New York magazine's Vulture website, which you can read HERE -- it's absolutely entertaining, but casually dismissive of the many true triumphs of the series.)

The most obvious irony was Katherine Rhumor's easy elimination by the evil prick of a poisoned-tipped pin in broad daylight in Central Park, as opposed to Donald Bloom's bungled hit that ends with Will being almost choked to death with a bath towel, furniture smashing everywhere, the neighbors undisturbed.

(I immediately thought of Scotty Evil in Austin Powers, International Man of Mystery, who, outraged, asks why Powers just cant be shot immediately, rather than being lowered into a pool of mutated sea bass and left for dead. Scott wails, "I have a gun, in my room, you give me five seconds, I'll get it, I'll come back down here, BOOM, I'll blow their brains out.")

Nevertheless, I don't buy the majority of criticism asserting that Rubicon moved too slow, or under-delivered. That the finale didn't wrap up everything was a smart set-up for a possible second season, but, more important, it asked that viewers participate and think about it for a bit, and fill in the blanks themselves. Become co-authors of our real, unfolding political drama.

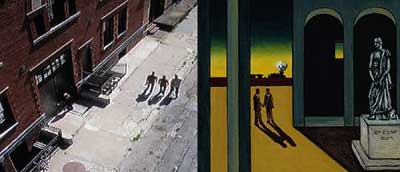

Maybe we did learn something after all. And the art-direction of the series -- the unsettling quiet streets, the long city shadows of the di Chirico-styled figures, the odd symbologies -- were all deeply satisfying.

Perhaps our best reward was Arliss Howard's character, Kale Ingram (seen at the top of this column), a Mephistophelian orchestrator of in the background, playing both sides -- Will's supposed protector, and former Black Operative. He revealed a universe of acting with just the slightest wedge of a smile.

As the next AMC offering, its visually stunning zombie thriller, The Walking Dead (beginning Halloween night), will be the next work of art to capture our imaginations.

I've seen the first two shows, and while it sets a questionable high for a grisly mess on standard cable, it also probes the underlying themes of free-floating anxiety and fear in our time, the mindless urban hoard we've found ourselves living amongst, and asks the question, What are the things we truly most want to live for?

As long as AMC will be providing us with smart, provocative dramas like these, consider me a viewer.

And a fan.