Forget the invention of the printing press, the telephone or even the electric light. This world was nothing until the invention of doppler weather radar. In fact, it's a wonder this world still spins, and wasn't ripped to cosmic shreds before doppler arrived and saved us from complete devastation...

So it indeed is appropriate that whenever they can, television meteorologists commandeer their station's airwaves and endlessly show their reverence to this most wonderful ever of humankind saviors, The Mighty Doppler.

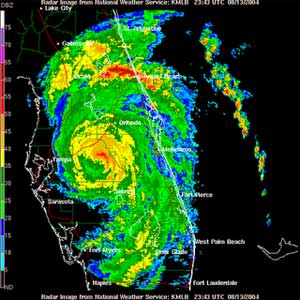

For more than 25 years, I have lived in Florida, where weather has replaced pastor Benny Hinn as television's saver of souls -- not to mention pets, wildlife, roofs, windows and, most important, ratings. Since 2004's hurricane season, TV has developed common law that proclaims lightning is license to worry, wind is reason to worry more, and the combination of the two is reason to just bend over and kiss your ass goodbye -- "unless you watch us."

Let a line of storms develop, and whatever was scheduled for the next day or so disappears from the screen so teams of men with rolled-up sleeves and loosened ties (and women wearing whatever might be the female equivalent of "this is serious" attire) play with their computers more than they did when, as younger children, they owned an Atari and a Frogger cartridge.

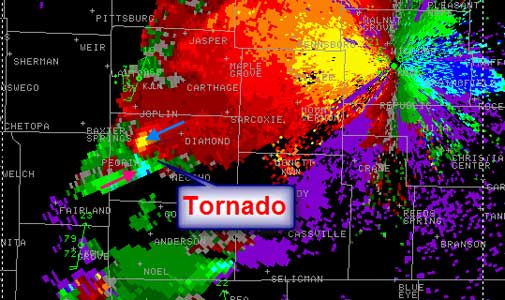

They show us the storm line from every angle, they show us the height of the storm, they play doctor, and look for dangerous purple round things hidden inside the radar that might make things even worse (gasp!). They also put so many trackers on the storm, their efforts surely rival the surveillance provided by drones flying over Afghanistan.

It's usually a litany of redundancies after what little news there was to report lies mostly motionless, doing nothing to qualify it as new news. It's also a game of chicken, as stations honor their pledge of allegiance to never be the first to resume regularly scheduled programming.

As long as there is one tree that might not remain upright, as long as dime-sized hail may inflate to quarter or half-dollar, as long as the wind speed exceeds that of a fully loaded bus moving up a 30-degree incline, there will be coverage.

In the city in which I grew up and lived until the mid-'80s, you knew some bad weather might develop if the old Cold War air-raid sirens were sounded. People then went to their basements, turned on the radio and left the safety of the basement only for bathroom breaks, drinks of water, snacks, to answer the phone, get the paper, or retrieve the trash cans that were blowing down the street. It's amazing we're still alive. But it's grand that we are, so we can witness the wonders of doppler at the drop of a hat (full of water).

I have been assured that this form of television ecstasy connected to radar screens happens all over the country. Tornadoes, snow storms, blizzards and other bad weather things, it seems, can't be fully dreaded unless there is much anticipation before their possible arrival.

That doesn't stop me from soliciting stories from you readers about the odd weather practices you have observed at your stations. (Our editor, David Bianculli, has vented on this website about the recent advent of "thundersnow." How are your local stations upping the weather-drama ante?)

Meanwhile, two former television news directors, both of whom teach ways to make broadcast journalism better, offer some professional and experienced perspective.

The technology exists, works and is important to viewers -- a fact reflected in how the number of viewers alway rises impressively when bad weather threatens, said Jill Geisler, now a faculty member at The Poynter Institute (journalism's equivalent of the FBI's Academy at Quantico or theology's seminary at the Vatican), and Scott Libin, who taught at Poynter for seven years before starting his own news consulting and instruction business.

People now know to turn to television in possible emergency situations for reliable information, and the weather department that does that job best contributes to a halo effect that raises the whole station, Geisler said. No money is made when weather coverage preempts all commercials. The halo effect can help make up for those losses in ordinary times, they said, by attracting more viewers. Higher ratings can translate to higher ad rates. And if stations were indeed as falsely alarmist as I have painted above, the public would see through the ploy, Geisler said.

What she said is a newsroom mantra of "First on, last off" is "always something of a dilemma" that can produce misjudgments.

"I wouldn't challenge that," Libin said when presented with the term "weather ecstasy."

A reason for that, he said, is that "most meteorologists see themselves primarily as scientists. At one time in relatively recent television history, radar was basic and black-and-white, the weatherman also was a staff announcer, and show-business clowning was written into his act. The leap from clown to scientist often skipped over a stop for learning about journalism, he said. "They want to give you every piece of information they see as relevant."

Excesses aside, how should any responsible station stop and start coverage with a developing story? "You can't say, 'That's all we know. We'll be back in 20 minutes.' New people are tuning in all the time."

One way to minimize weather overkill, Geisler said, would be to pool weather coverage the same way stations in some markets now pool helicopter coverage of a breaking story. But once the sizable expenditures were made in radar equipment and weather coverage became a bragging element, the chance of that happening has decreased mightily.

What options are there for viewers who brand this kind of weather coverage as excessive, silly, alarmist or exploitive -- or all of the above? Short of going on an exclusive bland video diet of Lifetime or TLC, the best solution is to just wait until this whole weather ecstasy thing blows over -- just like more than 90 percent of the storms the phenomenon celebrates seem to. And realize there are varying amounts of public serviceand personal revenue built into the picture.

But for now, unless you're "hunkering down" before an imminent storm, or on your way out to buy milk and bread before the snow arrives, please share some of your weather insights with the rest of us.