I grew up in a segregated community in a segregated America. Like many others, I learned during the late 1950s and into the '60s how wrong this was, and have tried since then to make amends for my ignorance. But as proven by PBS's current nonfiction series about slavery and its impact on Latin America, I remain more ignorant than I imagined...

I suspect I'm not atypical in thinking America stood shamefully alone in the world for its awful and divisive history of slavery and race relations, and that the slow resolution of race problems in the U.S. does at least something to remedy the wrongs that were done.

My limited knowledge of the history of slavery was revealed as I watched Black in Latin America on PBS. Of the more than 11 million people from Africa who were stolen from their land and families and made slaves during the Middle Passage, 450,000 ended up in the U.S. A huge majority ended up as slaves in Latin American countries, and this four-part series goes inside six of those countries to look at how the lives of slaves and their descendants differed in many ways from how slavery and its abolition played out in America.

The series, televised Tuesdays at 8 p.m. ET (check local listings), began last week with an examination of the surprising differences of how slavery has affected the residents of Hispaniola. In short, the Dominican Republic then and now, envisions itself as a country of Spanish history and culture.

Haiti, which is separated from its neighbor by a river, has a history and current culture built on its African heritage. Despite a common African past, the different mindsets have produced two very dissimilar citizens and governments.

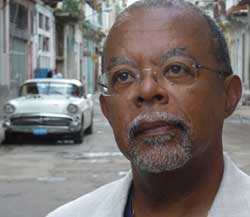

Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates Jr., the show's host, co-executive producer and writer, presents clear, illuminating and extremely interesting profiles of each of the countries (others are Cuba, Brazil, Mexico and Peru). Each has a different, complex history, which Gates explains through interviews with residents, observations of cultural events, and visits to places in each country.

(The Internet helps in correcting somewhat the tardiness of this review. The entire first episode can be watched HERE. The subsequent three episodes will be shown April 25, May 3 and May 10 -- all at 8 p.m. ET, but check local listings -- and also will be available on the same PBS video portal following the broadcast.)

The documentary's subject is not an easy one to explain, especially when the material will be previously unknown to many who watch. The clear and organized script tackles and minimizes that potential obstacle. If this and previous PBS productions of which Gates, right, has been part are examples of his teaching methods, it is easy to imagine his Harvard courses filling quickly. Excellent videography that has been expertly edited complement the script's attention-holding clarity.

The second installment, about Cuba (seen at top above), also may surprise most Americans. In the many decades since the revolution, the country has been pretty much a mystery. Its history and workings in regard to the nearly 800,000 Africans brought there as slaves and their descendants is even more the mystery. Early in his rule, Fidel Castro said discrimination in Cuba no longer existed. The program examines that claim and discovers its faults. The segments about Brazil, Mexico and Peru are equally illuminating.

By the time the series ends, we learn that the shame of slavery isn't confined to just our country and its aftermath has been markedly different in six of the Latin American countries that participated in its exploitation.

In a Gates interview that's available on the Web HERE he also notes a common trait:

"Each country except for Haiti went through a period of whitening, when they wanted to obliterate or bury or blend in their black roots. Each then had a period when they celebrated their cultural heritage, but as part of a multi-cultural mix, and in that multi-cultural mix, somehow the blackness got diluted, blended.

"So, Mexico, Brazil, they wanted their national culture to be 'blackish' -- really brown, a beautiful brown blend.

"And finally, I discovered that in each of these societies the people at the bottom are the darkest-skinned with the most African features. In other words, the poverty in each of these countries has been socially constructed as black. The upper class in Brazil is virtually all white, a tiny group of black people in the upper-middle class. And that's true in Peru, that's true in the Dominican Republic.

"Haiti's obviously an exception, because it's a country of mulatto and black people, but there's been a long tension between mulatto and black people in Haiti. So even Haiti has its racial problems."