[NOTE: The episode previewed in this article actually will air this coming Friday, Jan. 27 at 8 p.m. ET on ABC. So there's still time to swim with Sharks. - DB]

Sometimes a TV show -- even a reality TV show -- can break the bonds of its premise. Shark Tank, which returns to ABC Friday, Jan. 20 at 8 p.m. ET, had a pretty good premise to begin with. The season premiere, though, serves up a couple of engrossing surprises.

For newcomers, the show's formula (created in Japan as Dragon's Den by Nippon Television, and imported two years ago) is that wannabe entrepreneurs get a few minutes to pitch their ideas to five "sharks" -- wealthy businesspeople looking for new investment opportunities. After the pitch, the sharks circle and bite: What are your materials costs? What would prevent anyone else from offering the same service tomorrow? What were your first-year revenues? How do you plan to distribute this?

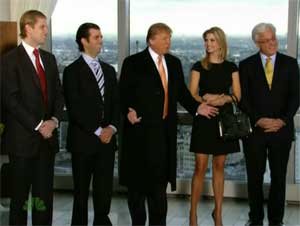

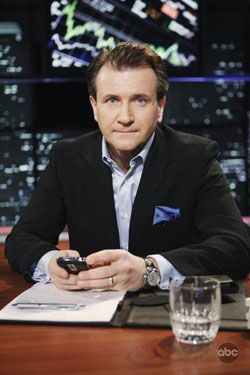

The capital-hungry contestant comes in with a proposal -- an offer to sell, say, a 25 percent stake in the enterprise for $85,000. The sharks are Barbara Corcoran (real estate); Robert Herjavec (tech); Daymond John (branding and fashion); Kevin "Mr. Wonderful" O'Leary (venture capital); and Mark Cuban (HDNet/Dallas Mavericks), who appears determined, on this show and elsewhere, to celebrity brand himself a la Trump. "Queen of QVC" retail innovator Lori Greiner will also circle the tank during three upcoming episodes.

One by one, the sharks either bail out -- the trademark terminator phrase on this series isn't "You're fired," it's "I'm out" -- or they counter-offer, as in, "I'll give you $50,000 for a 40 percent stake in your company." Losers walk away with zilch. Almost no one gets what she or he originally asks for. For those in between, we get to wonder who got the better deal. In the program's first two years, the sharks collectively sank (sorry) some $4 to $5 million of their money into new ventures.

The fun is in:

1) Vetting the business pitches along with the sharks. Who would ever want to buy that?! Or, how do I sign up?

2) When the sharks get snarly. In this episode, they call one pitchman "nuts," "absurd," and "insane."

3) Watching the sharks nip at each other. Think American Idol, with investment portfolios.

4) The real-time negotiations. One segment in this week's season premiere is high art. These sharks are not about to be oversold or out-negotiated, and it is a numb-skulled contestant who thinks otherwise. So watch as Mark Cuban outmaneuvers Dave Greco, who wants $90,000 for a minority stake in his corporate salesmanship system. Cuban offers a less generous package, adding, "You should take the deal and shut up." Greco does neither. None of the sharks like Greco's mobile apps strategy. In the end, bits of Greco flesh float in a reddened sea.

The way the show is pitched, we are supposed to hate the sharks.

"The only thing that really matters," announces the opening title sequence, is "money." And the sharks are not merely rich, they're "filthy rich." All this amid the Great Recession.

But the sharks are reasonable people, good at what they do. We can learn 11 times more about business from this program than from The Apprentice -- 111 times more than from The Celebrity Apprentice. While Trump and his slicked-back minions and addled has-beens are off conducting group therapy, the sharks here are asking shrewd questions.

Speaking of the Great Recession, the season premiere, in its final segment, turns downright riveting.

It features Donny McCall and his "Invis-a-Rack" -- a hideaway rack for carrying long things over the bed of a pickup truck. Folds up and hides away in seconds, as Donny demonstrates.

A soft-spoken, polite man from North Carolina, Donny tells the sharks how his wife didn't like the ugly permanent racks he was using, and "the Lord handed me this idea." The product will be made only in America, Donny insists. He wants to create jobs back in his hometown, where unemployment and suffering run deep. He can barely get the words out.

The sharks sit in silence.

But then they push him on the outsourcing question. What are his current production costs per unit? Suppose he could produce the Invis-a-Rack overseas much more cheaply -- cheaply enough to be picked up by a major distributor? Donny gives a couple of reasoned justifications, but his deeper motives are clear. God, country, community.

As the sharks continue, we, the audience, hear compelling arguments about the realities of globalization, and how an entrepreneur needs to first make sure the business is a success before he tries to change the world. Daymond John even has a slogan for this: "Make it, Master it, Matter." In that order.

Our heads are with the sharks, our hearts with Donny.

Suddenly, Robert Herjavec is talking about how his father, who passed away last year, had toiled in a factory his whole life. Herjavec -- an American success story -- knows exactly what Donny is feeling and trying to do. He, too, can barely get the words out as his chin quivers.

This moving and informative set piece on global capitalism could not have been scripted any better. It's a compelling piece of television.

In the end, does Herjavec, or do any of the other sharks, buy into Donny McCall's venture?

Dive in.