Let me begin this article the way I imagine Ken Burns would want me to -- with some context.

In 1993, William Jefferson Clinton was sworn in as the 42nd President of the United States. In the Middle East, PLO leader Yasser Arafat signed a peace agreement with Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. In Walpole, NH, and in New York City, filmmaker Ken Burns was putting the finishing touches on his definitive 18-hour documentary about America's pastime, Baseball. And in Philadelphia, a nine-year-old boy wept as his beloved Phillies lost the World Series in the bottom of the ninth...

Baseball would air on PBS the following year, the same year an unprecedented strike nearly shattered the game. Burns' brilliant documentary chronicled what, at the time, was the entire history of baseball, from its inception at the Elysian fields in the 1850s, to the very year my childhood dreams were broken.

I got over that loss, eventually, and realized that waiting a mere 15 years to witness my team get back to the World Series makes me one of the lucky ones. But in between those two fateful nights, I was also privileged to witness one of the most astounding and polarizing eras in all of baseball. This was the era of new franchises, astronomical salaries, devastating strikes, surges of international talent, the rebirth of the Yankees, the reverse of the Curse, and of course, the era of steroids.

Baseball the documentary, divided into nine parts called "innings," seemed to reach its finale just as baseball the sport was getting interesting again. Lucky for us, Ken Burns and co-director Lynn Novick came to the same opinion, and are now releasing The Tenth Inning, a two-part, four-hour follow-up special that covers the near-demise and the bittersweet reawakening of our nation's pastime. The program premieres Tuesday and Wednesday at 8 p.m. ET on PBS (check local listings).

This extra-inning sequel, for me, offers a chance to remove the purely historical lens, and to experience what so many viewers did with the original installments of Baseball. It allows me to relive the story of MY childhood -- to see MY heroes chronicled.

In the opening shots of The Tenth Inning, as a ragtime rendition of "Take Me Out to the Ballgame" washes over grainy film of baseball's late legends, we immediately feel the iconic Ken Burns signature evoking our deep-rooted sense of the past.

But as the photos turn to modern highlight clips, we are introduced (via Keith Olbermann, one of the many new faces in The Tenth Inning) to an interesting notion. Part of the magic of watching a game like baseball, he says, is that what you are witnessing is virtually the same exact game that was being played in the 1860s. Football may have replaced baseball as America's favorite sport, but baseball will always be America's pastime, and for good reason. More than any other sport, baseball is as interested in its past as in its future.

While other sports strive to evolve and improve, baseball remains largely unchanged, giving it a sort of timeless perfection that you can't help but appreciate and respect. As Olbermann points out, "As you come into to the start of a game or a season, or even the start of your own fandom, you feel as if you are joining the river midstream."

After a brief introduction, we are immediately exposed to one of the most beautiful moments of the entire four hours. In it, Jose Feliciano's soulful 1968 cover of "The Star Spangled Banner" plays over clips of children playing stickball and pickup games on the streets of the Dominican Republic. In one brief montage, we understand the gift that baseball has given to the world, and, in that same moment, foreshadow the gifts that these impoverished nations would soon give back to baseball.

When the song winds down, writers Burns, Novick and David McMahon pick up the story right where Baseball left off. Barry Bonds signing the most lucrative free agent contract up to that point. Expansion teams rising with new markets. International fan bases, new stadiums, the rise of cable TV. And the hint, just the ever-so-subtle hint, that players were starting to play with an unprecedented combination of speed and power.

Every minute of The Tenth Inning is beautifully told and effortlessly compelling, but some moments stand out as particularly noteworthy.

For example, It was wonderful to re-watch Cal Ripkin, the man who restored honor to the game after the deplorable strike, wave to a standing ovation after setting the record for consecutive games played.

It was wonderful to watch Joe Torre's eyes fill with tears after struggling his entire adult life to make it to "the top of Everest," and then to get there four more times in five years.

It was equally wonderful to watch rival fans, after 9/11, holding up signs saying "We Are All Yankees" as a wounded city's team neared a possible championship.

But the moment that truly brought tears to my eyes was when we are told the stories of victorious Red Sox fans placing notes and flags and scorecards at the graves of family members who lived and died without witnessing a championship. A camera shot pans in on a card that a son left for his father: "They did it, Dad," it reads. "Rest easy."

Of course, all the lighter moments are present as well. The brawls between the Sox and the Yankees. Mets fans throwing dollar bills at greedy players post-strike. The infamous fan interference at the Cubs' NLCS game. The Latin invasion of Pedro, Manny, Sosa, and Papi. The Japanese invasion of Ichiro and Matsui. The ridiculous salaries, and the even more ridiculous stats.

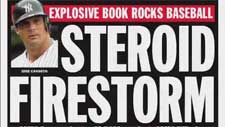

Which brings us to the underlying narrative of the entire story. By 1990, when Congress passed a law making it a felony to traffic anabolic steroids, the Olympics, NCAA and NFL already had banned them. But baseball played by its own set of rules, in a world where the players were virtually untouchable.

Burns weaves the hints and implications throughout the four hours, sometimes subtly, sometimes more directly. But through his careful storytelling and his always-impressive knack for letting his interviewees contextualize, he finds a way to humanize the players involved, shedding an ambivalent empathy on the whole situation.

"Who in the whole country wouldn't take a pill to make more money at their job?" Chris Rock asks. Staring [presumably] at Burns, he adds, "If I said, 'Hey, there's a pill and you're gonna get paid like Steven Spielberg,' you would take the pill... You just would."

While by no means excusing the tarnishing effects on homerun records and the image of the game, Burns simply reminds us that this was a problem far more pervasive than most people thought. Untie the one string of Barry Bonds by adding an asterisk to his records, and you then have to untie endless other strings -- the players who pitched to him, the other sluggers against whom he competed -- until almost the entire league's statistical legacy has become unspooled.

Burns shows the whole story chronologically, from McGuire's rookie season home-run record to his crushing of Maris' seemingly untouchable single-season record, to his pitiable testimony before Congress, where he pleads the guilt-ridden Fifth.

We see Barry Bonds crack a long ball to tie (and later surpass) McGuire's astronomically inflated and dubious single-season home run mark -- aptly, at Enron Field -- and later see him quietly surpass Hank Aaron's all-time home-run record, while disenchanted crowds boo him every game along the way.

We see legends become suspects, and records become unofficial asterisks. But even more interestingly, we see a nation of fans move on. Regulations tightened up, and anabolic steroids all but disappeared. The games went on. The fans came out. And baseball, while always changing on some level, remained, at its core, exactly the same.

A brilliant piece in the film cites a quotation by English poet John Keats on what he felt was Shakespeare's greatest attribute in writing, something Keats called "negative capability." Simply put, it's the ability to remain intentionally undecided between two conflicting ideas -- to see things for exactly what they are without assigning the morals of right and wrong. At the end of the day, this is exactly what Burns has accomplished with this piece.

He doesn't create heroes and villains, or choose sides, or reach any permanent conclusions. Instead, through the good and the bad, he simply tells the story as honestly and objectively as he can, infusing it with a clear passion and respect for what he regards as "still the best game that's ever been invented."

And as I saw all the stories I've experienced since childhood play across the screen, stamped with that unique Ken Burns touch, it suddenly hit me. The Tenth Inning is by no means an ending to anything.

Rather, it's just another chapter in an ongoing history, perfectly preserved for anyone who wants to join the river midstream.