There’s a compelling case that no entertainer of the 20th century could multitask better than Sammy Davis Jr.

There’s a compelling case that no entertainer of the 20th century could multitask better than Sammy Davis Jr.

Director Sam Pollard makes that case, or rather, lets Davis make it, in Sammy Davis Jr.: I’ve Gotta Be Me, a PBS American Masters documentary that premieres Tuesday at 9 p.m. ET (check local listings).

Pollard takes us through Davis’s whole career, back to costarring with Ethel Waters as a 7-year-old in the 1933 film short Rufus Jones For President.

Young Sammy’s tap dancing was a show-stopper then, and he’s no less breathtaking in the documentary’s final dance clip, filmed with Gregory Hines at a tribute evening shortly before Davis died in 1990.

Those bookends suggest Davis may have been a hoofer at heart, and perhaps he was. He had bigger dreams, though, and the in-between years saw him score as a singer, an actor, a comedian, a vaudevillian, a movie star, a TV star, a stage star, an impressionist and an all-around show biz personality.

It’s hard to think of anyone who did more things better. It’s less difficult to understand why Davis never got full credit, and I’ve Gotta Be Me examines the many reasons, embedded both in his own complicated character and in the nature of mid-20th-century show biz, which is to say the nature of mid-20th-century America.

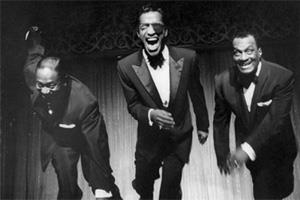

Davis was a terrific singer who had the misfortune of being best known for the annoying novelty tune “Candy Man.” As a nightclub entertainer, his amazing range of talents was subsumed into his identity as the third anchor of the Rat Pack (right), alongside Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin. In the movies, or on television, Davis never got the showcases afforded to colleagues with whiter skin tones.

Davis was a terrific singer who had the misfortune of being best known for the annoying novelty tune “Candy Man.” As a nightclub entertainer, his amazing range of talents was subsumed into his identity as the third anchor of the Rat Pack (right), alongside Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin. In the movies, or on television, Davis never got the showcases afforded to colleagues with whiter skin tones.

Davis often cracked that as a black and a Jew, he was a one-man minority who could clear out any neighborhood. It was a funny joke built on unfunny truths, and his black audiences, at least, understood that show biz had its own unspoken strictures.

After Davis kissed a white woman, Paula Wayne, in the stage production of Golden Boy, picket lines formed outside the theater.

After he married white actress May Britt, President-Elect John F. Kennedy barred him from appearing at any 1961 Inaugural entertainment events. Democrats still needed the Southern segregationist vote, and Kennedy didn’t want to offend them.

In a further cruel irony, those events had been largely organized by Sinatra, who had originally invited his Rat Pack colleague to appear and then did not challenge Kennedy on the disinvitation.

That’s a small taste of the dish Sammy Davis Jr. had been served.

Still, Davis remained with the Rat Pack through the mid-'60s – on stage and in film. While he and Sinatra had an up-and-down relationship, there was genuine underlying respect and affection, and a decade later Davis joined Sinatra in migrating to the presidential campaign of Richard Nixon.

What happened next is too well known. After Nixon praised Davis at a campaign rally, Davis impulsively rushed over and gave Nixon a hug.

This image sent a deep chill through a black community that had long loved the kid from Harlem who made it to the top.

Davis spent years rebuilding that reputation, tough years when his style of old-school entertainment was also being eclipsed by a newer wave.

Happily for Davis, that wave included Michael Jackson, who knew and loved Davis’s work – and in some ways was a modern song-and-dance incarnation of Davis.

Jackson helped restore some of Davis’s cool, even as Davis himself spent his last decade fighting his way through a final maze of contradictions.

Jackson helped restore some of Davis’s cool, even as Davis himself spent his last decade fighting his way through a final maze of contradictions.

He had serious cocaine and alcohol problems. He needed a hip replacement. Never a fiscal conservative, he was running out of money.

At the same time, he kept working. Davis, Sinatra and Liza Minnelli headlined a hit reunion tour, Minnelli filling in after Martin dropped out. Davis played an iconic hoofer in the 1989 movie Tap, and the reverence in which other real-life dancers held his work was embodied in a live tribute show when Hines dropped down and kissed his shoes.

In the end, Davis’s legacy is far too complex for one 90-minute documentary to distill. Pollard does a solid job with the time he has, hitting the main points and showcasing as much vintage film as possible.

What’s missing aren’t critical milestones as much as detail on Davis’s own life and the bubbling cauldron of American race relations and attitudes over the three generations it spanned.

Davis grew up performing with his father and godfather in the Will Mastin Trio (below), a dance act straight out of old-time vaudeville.

As I’ve Gotta Be Me notes, little Sammy’s professional immersion was so complete that he never attended a day of school. Everything he knew, he learned on the road.

His mother, Elvera “Baby” Sanchez, was a dancer who spent those years pursuing her own career.

I’ve Gotta Be Me notes how Davis was brutalized during Army training when he was placed in the first integrated unit.

Things weren’t so physically threatening when he integrated the Rat Pack, but Davis faced some of the same broader challenges, like how to be seen as an entertainer and not a black entertainer.

It had to be frustrating since he’d never drawn that line himself. His hands-on mentors, besides his father and Will Mastin, included Bill Robinson, Jerry Lewis, and Eddie Cantor.

It had to be frustrating since he’d never drawn that line himself. His hands-on mentors, besides his father and Will Mastin, included Bill Robinson, Jerry Lewis, and Eddie Cantor.

As a member of the Rat Pack, Davis routinely went along to get along, laughing it up at one-liners from Sinatra and Martin about race riots or the Ku Klux Klan.

It was in service, I’ve Gotta Be Me suggests, of being a star. Pollard found a press conference at which Davis explains he doesn’t want to be the guy next door. He wants to be the guy in the spotlight, living large; the one everyone watching would like to become.

That path was a lot harder for anyone of Davis’s skin color. It just was, and in many ways it still is.

In November 1954, Davis nearly died in an auto accident outside Los Angeles. He lost his left eye and finally recovered amid an outpouring of support by fellow entertainers from Ella Fitzgerald to Marilyn Monroe.

I’ve Gotta Be Me recounts how, for his first public performance after the accident, he returned to LA’s hottest Hollywood celebrity nightclub, Ciro’s.

His first public appearance after the accident, however, came earlier, 3,000 miles east, at Harlem’s Apollo Theater. He sat on a stool with a microphone and a cup of coffee – and, okay, probably a cigarette – and talked about how, now that he knew he was coming back, he wanted first to see his people, the ones who had been behind him from the start.

A few years earlier, Sinatra had recorded a famous version of the Earl Robinson anthem whose lyrics go “The house I live in / That’s America to me.”

Davis never recorded it. He just lived it.