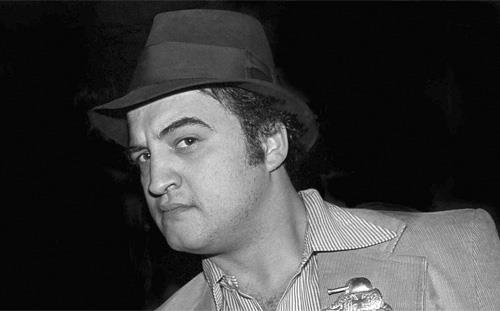

In 1984, two years after comedian John Belushi was found dead in a Los Angeles hotel cottage from a fatal mashup of heroin and cocaine, journalist Bob Woodward wrote Wired, a book that painted Belushi as a talented, obsessively driven wild-man whose lethal excesses more or less inevitably caught up with him.

Belushi's widow, Judy Jacklin Belushi, always considered Woodward's book sensationalistic and unfair, perhaps in part because she was portrayed as, in many ways, an enabler.

Now, 38 years later, Judy has offered her countermove: a new documentary simply titled Belushi, directed by the sympathetic R.J. Cutler and premiering Sunday at 9 p.m. ET on Showtime.

Interestingly, Belushi doesn't really dispute the characterization of Belushi as a compulsive addict who threw himself headlong into everything, whether it was a Saturday Night Live character or controlled dangerous substances.

Rather, it tempers that picture with snapshots that suggest he had another side, more introspective and perhaps softer. His love letters to Judy through their long courtship and marriage are streaked with veins of insecurity and warm affection, in notable contrast to the manic swashbuckling of his most famous characters from Saturday Night Live, Animal House, and even The Blues Brothers.

Belushi takes us through his childhood with distant parents, his early fascination with performing, his love for comedians like Jonathan Winters and Bob Newhart, and his methodical climb up the comedy ladder from the small-time to the top of the big time.

His brother Jim says John once told him that the secret to performing was to enter the stage like a bull charging into the ring. That may not be a universally applicable formula, but it sure worked for John Belushi. Particularly on Saturday Night Live, a major part of his fascination for viewers was that they never knew what a Belushi character would do next, except that it might take an elephant tranquilizer to calm him down.

As his star rose, he was also susceptible to performer insecurities. He resented Chevy Chase becoming the breakout star of SNL's first season, and Chase's brief interview comment here suggests that while they had worked together for years before SNL, their relationship never rewarmed.

Belushi wasn't the first performer, or the last, who dealt with that insecurity through escapes like drugs.

With drugs, as with everything else for Belushi, once he started, he was all in. Friends say there were stops and starts, but that over the years, his drug and alcohol use only escalated.

There's every indication he felt genuinely close to his wife and that he really was best friends with his fellow Blues Brother, Dan Aykroyd. But there seems to have been no effective check on his indulgences.

One of Belushi's other friends recalls here how, late at night, he would snort cocaine on SNL producer Lorne Michaels's desk. Michaels wasn't there at the time, but the image underscores the dangerous fact that when someone gets to be a big enough star, not many people say "no."

Belushi also suggests that, not surprisingly, John had a restless side. Not long after the Blues Brothers movie, he gave away his blues records, saying now he only cared about the emerging punk movement. He also wanted to shake his image as the wild-man comic sketch artist and become a more serious actor.

When that didn't happen overnight, he started spending more time with his good friends the drugs.

Belushi doesn't explicitly feature Judy, and she doesn't talk about her relationship with John except in glancing hints. The word "codependency" makes one brief, passing appearance, with no further explanation.

She says she wasn't with him on that last fatal trip to California, where he was shooting a movie, because her psychiatrist urged her to stay at their home in New York and "focus on myself."

Aykroyd says he spoke to Belushi a few days before the fatal overdose and was concerned enough that he planned to fly to California to bring him home. That trip got delayed until it was too late. Aykroyd also says he told Belushi he was working on a new movie script that would "solve all our problems." That script became Ghostbusters.

Belushi doesn't dwell on the end, preferring – legitimately – to focus on earlier, better days. Still, it's noticeable that it never mentions Cathy Smith, the woman who was with him during his extended fatal binge and who said she gave the injection that killed him.

Let's guess that the omission of Smith, who died in August at 73, does not displease Judy Jacklin.

Belushi re-creates a number of pivotal scenes from John's life with animation. It also includes interviews with many of the people who knew him over the years, including Aykroyd, Harold Ramis, Michaels, and Jim Belushi.

Their consensus is that he had a marvelous talent and incredible charisma and that if you caught him at the right time, he could be a nice guy. They also recall him as ambitious, tightly wired, and often troubled, as if he kept the pedal to the metal without being sure where he wanted to go.

Consider Belushi one of the works that will get you closer to the John Belushi that its title character never quite found.