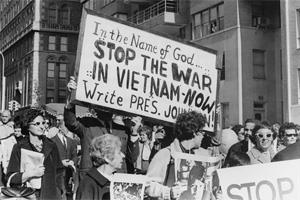

It’s the summer of ’68 when The Vietnam War picks up the thread in “The Veneer of Civilization.” The home front is restive. Americans of draft age face difficult decisions and hard moral choices in increasing numbers, even as police and demonstrators clash in Chicago. Richard Nixon, an also-ran from a previous presidential campaign, is poised to win the presidency on a campaign promise of law-and-order at home and peace overseas.

Neither promise will go according to plan.

We know this, of course, but once again Ken Burns and his co-director Lynn Novick are not interested in the “what” or “where” so much as the “how” and “why.”

First a programming note. Tonight’s installment and the three that follow all run two hours.

That’s a lot to take in at one time. If there’s a knock to be made against The Vietnam War, it’s that the two-hour episodes can be a grind — not because they seem drawn out or padded but because there’s so much emotional terrain to cover, so many highs and lows to deal with. It’s almost too much to absorb in a single sitting, let alone find the time to think and let it sink in.

The Vietnam War is not one of those documentaries one watches and then forgets before the next NFL game. It gets under the skin and burns into the consciousness. Over two hours, it can all be a little overwhelming — especially when, as in “The Veneer of Civilization’s” case, the focus falls on 18- and 19-year-olds drafted into an unpopular war, a war many of their friends, neighbors and classmates are protesting against.

Narrator Peter Coyote: “Young men all over the country would continue to face questions and choices their fathers rarely had to face when asked to fight in other wars. What obligation does a citizen owe his country? What should one do when asked to fight a war in which one did not believe? How does a soldier distinguish between a shadowy enemy and the Vietnamese civilians he is supposed to be defending? The coming summer of 1968 would be one of the most consequential in American history.”

“The Veneer of Civilization” opens with a TV newscaster reciting casualty figures — 299 Americans dead, 353 South Vietnamese dead, and 2,019 “enemy” dead.

Today, we know those numbers were largely bogus, but the fact that this is the way the nightly news chose to cover the war highlighted an even larger problem: War is not a sports event, where the team with the highest score wins. The question that needed to be asked — that Burns and Novick allude to throughout The Vietnam War’s 18 searing hours — is that if a people who were willing to lose 10 or 20 of their friends’ and loved ones’ lives for every one life lost on the other side, and yet keep on fighting, how could they lose — especially when the stakes were the survival of their homeland and all they held dear.

The first song heard in “The Veneer of Civilization,” just four minutes into the program, is The Beatles’ “Revolution,” played against newsreel footage of riots in America’s streets. Like so many of Burns and Novick’s music choices, “Revolution” — written by John Lennon but credited to both Lennon and Paul McCartney — is both an inspired and terrifying choice. (In an interview with TVWW, Burns admitted he worried that the rights to Beatles songs would be tough to get; as it happened, McCartney and the Beatles rights-holders could not have been more accommodating. Burns’ past history, The Civil War, Jazz and The War, preceded him; McCartney knew, without asking, that The Vietnam War would not be trash.)

Lennon wrote “Revolution” in 1968, inspired by the political protests roiling at the time; his lyrics, controversial at the time for both left and right, expressed doubt to the tactics of protest (“Count me out”) and yet became an anthem for the anti-war movement, despite those protestors who saw it as a betrayal of their cause.

That underlying question — for or against, right or wrong, good or bad — is what drives the entire Vietnam War project.

Burns has said The Vietnam War provides no answers, easy or complicated. Rather, he hopes anyone watching it will think hard about the questions it raises, and how that might inform the choices and decisions we make today.

Richard Nixon is elected president 25 minutes into “The Veneer of Civilization’s” two hours. It was, we’re reminded, one of the most extraordinary comeback stories in US political history.

Nixon made the case for himself as the man who could bring a fractured America together, and bring an honorable end to the war in Vietnam.

There’s an astonishing piece of footage of Nixon’s acceptance speech at the 1968 Republican Convention in front of a smiling Ronald Reagan, and it’s impossible to watch today and not feel a pang of recognition. A chord of electricity, running straight up the spine.

This is what Burns is truly great at — past as prologue.

“When the strongest nation in the world can be tied down for four years in a war in Vietnam with no end in sight,” Nixon begins, “when the richest nation in the world can’t manage its own economy, when the nation with the greatest tradition of the rule of law is plagued by unprecedented lawlessness, when a nation that has been known for a century for equality of opportunity is torn by unprecedented racial violence, and when the president of the United States cannot travel abroad or go to any major city at home without fear of a hostile demonstration, then it’s time for new leadership for the United States of America.”

We now know there would be no peace at home, nor in Vietnam, not for years yet. The Vietnam War, much like the war it depicts, will go on. To borrow a lyric from Buffalo Springfield — used in “The Veneer of Civilization” — nobody’s right if everybody’s wrong.

TV Worth Watching will preview “Episode 8: The History of the World (April 1969 - May 1970)” on Tuesday. The Vietnam War continues Wednesday and concludes Thursday, Sept. 28. All nights PBS at 8 p.m. ET. Check your local listings.