“My older sister and I one time were watching the movie So Proudly We Hail! on TV,” ex-Army nurse Joan Furey recalls in the opening moments of “The History of the World,” tonight’s latest chapter in The Vietnam War.

So Proudly We Hail!, filmed in black-and-white in 1943, tells the true-life story of a group of military nurses who served — and barely survived — the Japanese invasion of Bataan and Corregidor in the Philippines during World War II.

“It was the first probably time in my life that I realized that women could do brave and courageous things,” Furey says. “it wasn’t just something men could do.”

Furey (left), from Port Jefferson, NY, had wanted to be a nurse ever since she was a small child. She attended nursing school, and when a high-school classmate was killed during the Tet offensive, she signed up for military duty, to do what she could for the wounded.

What she found was not quite what she expected. This was not China Beach, or a World War II movie on the TV. This was real.

She was posted to the 71st Evacuation Hospital in the heart of Vietnam’s Central Highlands. Part of her tour involved treating wounded North Vietnamese and Viet Cong soldiers who sometimes spat at the doctors and nurses trying to save their lives. Whenever the hospital came under mortar fire — more often than not in the dead of night — Furey stayed with the most seriously wounded men, in the ICU.

Her testimony is powerful and wrenching, and it has the effect of pulling the viewer straight into the heart of “The History of the World.” Tonight’s two-hour installment takes in the 12 months between April 1969 and May 1970 and it features some of the most powerful and haunting moments yet. A rising tide of resentment and protest in the US homeland boiled over, even as the leaders and decision makers in North Vietnam appeared to be stoic and impassive, no matter what doubts and concerns they harbored in private.

Richard Nixon had his own private doubts. Despite his outward bluster, deep down Nixon knew that military victory was virtually impossible, that things would have to be settled at the bargaining table in Paris. He had to find a way to extricate America from Vietnam without seeming to surrender. He believed he could use his reputation as an implacable anti-Communist to his advantage in the negotiations with Hanoi.

“We’ll just slip the word to them,” he was recorded as saying. “You know, ‘Nixon’s obsessed about communism. We can’t restrain him when he’s angry, and he has his hand on the nuclear button.’ And Ho Chi Minh will be in Paris in two days, begging for peace.”

Ho Chi Minh had other ideas, though — Nixon’s ‘hand on the nuclear button’ or no. As with the presidents who came before him, Nixon’s efforts to end the war would only end up widening it.

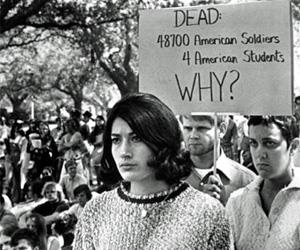

Protests on university campuses across the US homeland grew in both size and intensity, and “The History of the World” ends in a shattering moment in American history — the shooting of unarmed students at Kent State University by the Ohio National Guard, on May 4, 1970 (right).

“History of the World” is not an idly chosen title, and the issues and historical context of Kent State are not limited to a mid-sized public research university on the banks of the Cuyahoga River in a Midwestern state bordering the Great Lakes region. Little more than a week into its airing on PBS, parts of The Vietnam War have already been screened in Southeast Asia, including Hanoi and Ho Chi MInh City itself. A 10-hour international cut of the film has been licensed to 43 countries around the world, the most ever for a Burns film prior to its premiere. Arte France, RTE Ireland and the BBC in the UK all committed to premiering the film this very week, right now, even as the US audience has three more nights to the end.

Surviving war is “the history of the world,” former Marine radio-operator Tom Vallely recalls quietly, little more than 25 minutes into tonight’s two hours. Back in the day, President Nixon and his national security advisor Henry Kissinger resolved to redefine what victory would look like, even if it meant — in Kissinger’s words — “unilateral withdrawal.”

One of Burns’ signatures as a filmmaker is the way seemingly random details come together and coalesce in often unexpected ways, over the course of an entire film. A young nurse’s experience in Vietnam’s Central Highlands may seem to have little to do with the cloistered meetings between a US president and his national security advisor in Washington, DC, just as hushed conversations in the corridors of power seem to have little to do with sudden, deadly gunfire on a university campus in the US Midwest.

“The History of the World” features many such seemingly disconnected threads: corruption in South Vietnam (surplus US military equipment was a big mover on the Saigon black market); what was acceptable in war and what wasn’t (“I didn’t need Vietnam to teach me that,” Vallely says; “I learned that in Sunday school”); racial tensions between blacks and whites in-country, on the front lines, and back home, in the American heartland; Woodstock (Country Joe and the Fish singing, “What are we fightin’ for/Don’t ask me, I don’t give a damn/Next stop is Vietnam”); the My Lai massacre, Lt. William Calley Jr. and the until-then unheralded Army captain and helicopter pilot Hugh Thompson Jr., who would prove instrumental in ending the massacre and bringing the perpetrators to justice; and, at the very end, the harrowing final act of Kent State — 67 rounds in 13 seconds, two young women, Allison Krause and Sandra Scheuer, and two young men, Jeffrey Miller and William Schroeder, unarmed, shot down and killed, and a single protest sign: “Dead: 48,700 American Soldiers; 4 American Students. WHY?”

Seemingly disconnected, yes, but linked by one common thread — a divisive war that would tear two countries apart, worlds away from each other, on two separate continents.

The Vietnam War has already produced a soundtrack album of songs from the era. In a Sept. 15 essay for this parish, TVWW scribe David Hinckley penned a fine piece about the B-sides that appear in the film but didn’t make the final cut onto the album.

“The History of the World” is full of such B-sides. Of all the episodes in The Vietnam War so far, “History of the World” is deserving of an album in its own right. One after another, some of the most poignant, moving songs of the era play as a backdrop to a montage of catastrophic events throughout the back half of 1969 and early 1970 — Joni Mitchell’s “Woodstock” (“I came upon a child of God/He was walking along the road”); The Beatles’ “Blackbird” (“Blackbird singing in the dead of night”); B.B. King and Roy Hawkins’ “The Thrill is Gone” (“The thrill is gone/It’s gone away for good”); Bob Dylan’s “Subterranean Homesick Blues” (“You don’t need a weatherman to tell you which way the wind blows”); Neil Young’s “Ohio” (“Tin soldiers and Nixon coming/We’re finally on our own”); John Fogerty’s “Bad Moon Rising” (“I see a bad moon a-rising/I see trouble on the way /I see earthquakes and lightnin’/I see bad times today”), and too many more to name here.

“No 19-year-old wants to die to maintain the credibility of Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon,” Army veteran Vincent Okamoto explains quietly, midway through “History of the World.” “ So within a relatively short period of time, the guys are saying, ‘Look, we shouldn’t be here, but we are. So my only function in life is to try and keep you alive, buddy, and to keep my precious ass from being killed.

“And then go home and forget about this.’”

As The Vietnam War shows, there is no forgetting.

Perhaps, though, in the fullness of time, there is some small way of accommodating it.

Burns himself has said in interviews that, for those who fought in the war and have had a hard time forgetting that which they’d rather forget, his hope is that The Vietnam War might provide some peace of mind, even if only in some small way.

“When you kill someone for your country,” Army medic Wayne Smith recalls, his voice shaking,“all things change.”

TV Worth Watching will preview “Episode 9: A Disrespectful Loyalty (May 1970 - March 1973)” on Wednesday. The Vietnam War concludes Thursday, Sept. 28. Both nights PBS at 8ET/PT. Check your local listings.