[Bianculli here: Contributing writer Tom Brinkmoeller follows a lot of public TV and informational cable TV shows. And when some of them began disappearing from his television set, he decided to keep following them, and find out where they went and why...]

Recession Puts TV Innovators on Endangered-Species List

It's safe to guess that public-TV icon and master carpenter Norm Abram and producing legend Steven Bochco seldom, if ever, have crossed paths. Just as it's a pretty sure bet that TV master chef Sara Moulton and TV legend Sid Caesar never talked television. Still, these four equally share the title of TV innovator.

Bochco set all-new criteria for prime-time drama when he co-created Hill Street Blues in the early '80s; Caesar starred in, and was the driving force behind, groundbreaking live television shows in the 1950s.

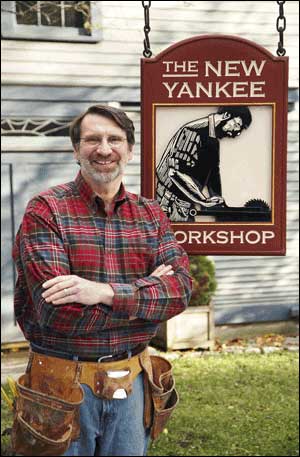

Abram was part of a small team that gave birth to and grew how-to television on a national scale when This Old House debuted -- two years before Hill Street. For 21 seasons, starting in 1989, Abram further built his reputation as the standard by which all TV home-improvement shows should be measured as host of The New Yankee Workshop. A couple of cable networks overflow with shows that trace their heritage to these two long-running Abram shows.

Moulton's groundbreaking was done at a kitchen counter. Caesar's many once-a-week programs were masterpieces of timing, planning and improvisation -- all done without the safety net of videotape. For six years, Moulton hosted the hour-long Cooking Live series on the Food Network five nights a week -- and the word "live" means just that: with sharp knives, live flames and real-time call-in questions from viewers.

For a while she did two live shows a night. As ER and The West Wing proved when those series went live in prime time, a live show done well is excitingly creative. When Cooking Live ended in 2002, there were more than 1,200 of them in Food Network's library. It's a record that probably never will be duplicated.

Despite their accomplishments, the visibility of these two innovators has decreased. Abram recently said he regained about 150 days a year when New Yankee Workshop stopped production and he turned his TV efforts only to This Old House. Moulton, who has a unique ability to make cooking watchable, understandable and easy, currently hasn't a show in production. Her two cookbooks, plus a third that will be published in April, are the current ways to connect with this extraordinary teacher.

It wasn't Moulton's idea to end Cooking Live, she said in a recent interview. Innovation lost its cachet at the Food Network years ago. The network that once hosted noted contemporary chefs sharing their expertise has moved far from that Julia Child end of the spectrum to shows that feature home cooks, nearly ubiquitous competition programs and, as Moulton pointed out, an abundance of female cleavage.

"The target audience," she said, "appears to have shifted to 15-to-35-year-old males."

As the focus changed, chefs such as Mario Batali, Ming Tsai, Emeril Lagasse and Gale Gand disappeared from the network. Moulton didn't leave immediately. She moved to a half-hour taped program, Sara's Secrets. The series was in production for about three years and Food Network used reruns for another two years.

After leaving the network in 2005, she hosted Sara's Weeknight Meals on public television. Though production ended on that series, she hopes it may restart as the economy improves and underwriters for public-TV shows reappear. That same weak economy contributed to the folding of Gourmet magazine last year. Moulton was executive chef of the publication, and as it sunk it also pulled under a pending syndicated series, Ask Gourmet with Sara Moulton.

Even though it was a lot of hard work, Cooking Live remains a personal favorite with Moulton:

"It was the perfect show. I would love to do it again."

There's a small chance the company that owns the Food Network might make that happen. Scripps Networks plans to launch the Cooking Channel later this year. When asked if a live cooking show might make the new network's schedule, a Scripps representative said, "That's certainly something that's in the (potential) mix."

Abram is hoping for The New Yankee Workshop to return to the air in a different way. When he and producer Russell Morash began the series in 1988, they guessed there were enough woodworking projects to take it "through four years, and that would pretty much do it," Abram said. Instead, it stayed on the PBS schedule for 21 years, with the last two seasons highlighting repackaged early episodes.

"We pretty much accomplished what we set out to do. And I wanted some more free time," he explained.

Abram and Morash believe the early episodes are just as good as when they were new, but the financial support for the repackaged shows evaporated, and this is the first year in 22 that hasn't seen a new Yankee season. For now, an early episode is posted each week on the show's Web site, which you can find HERE. And if the Web traffic is strong enough, underwriting may reappear for the series, he said.

Abram's work, like Moulton's, focuses on high quality and accessibility versus flash and the half-hour fix. It's one type of programming that makes TV worth watching. A better economy may keep that standard from being forgotten.

--

TV Worth Watching contributor Tom Brinkmoeller, who is neither a chef nor a carpenter, tries to improve his meager skills by watching real artists at work.