It’s one of the toughest questions there is, as a fan. How do you separate an actor from the character he, or she, plays on TV? Can you separate the two? Is it even right to try to separate the two?

Bill Cosby was found guilty last week on three counts of aggravated sexual assault. He’s expected to appeal while he awaits sentencing. Even if Cosby should win on appeal — and it’s hard to imagine what the legal grounds might be — the die is cast. Just this past Thursday, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences — the prestigious organization that runs the Oscars — announced it had expelled Cosby from its organization. The academy said its board members made the decision after a vote on Tuesday.

Everyone who has watched TV over the past 40 years has memories — mostly fond — of what Cosby meant to them. For most, that’s probably The Cosby Show. For me, it was I, Spy.

I Spy was one of my defining coming-of-age TV dramas while growing up, though I came to it late: I was just five-years-old when I, Spy debuted in the fall of 1965. Like many before me, I discovered I, Spy in reruns, in the mid- to late 1970s.

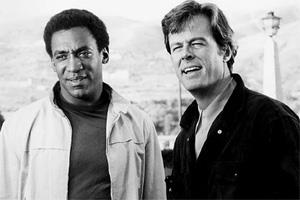

The globe-hopping adventure starred Robert Culp and Cosby as undercover CIA operatives traveling the world, making far-flung countries safe for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. I, Spy ran for three seasons in all, between September 1965 and April 1968. Over the years, I, Spy clocked a total of 82 episodes. The series was filmed not on a back lot in Burbank but in cities all over the world including Venice, Tokyo, Madrid, Florence, Hong Kong, Athens, Rome, and Fez, Morocco, at what must have been a shocking cost to the studio and network NBC, even in mid-1960s money.

Eighty-two episodes spread over three seasons is a blink-of-an-eye in present-day terms, of course, when a Law & Order: SVU can push past 19 seasons and more than 400 episodes, while The Simpsons sets a new benchmark every week it seems, now at 29 seasons and more than 600 episodes.

And yet, even in that relatively short span of time, I Spy left an indelible mark on the culture.

And not just because Big Bang Theory creator Chuck Lorre named his Big Bang leading men after I Spy’s irascible, over-the-top, larger-than-life studio mogul, Sheldon Leonard. (True story: Lorre, no shrinking violet himself, considers Sheldon Leonard to be one of the most influential moguls in the medium’s history, the Samuel Goldwyn and Louis B. Mayer of the small screen.

I Spy wasn’t simply eye-catching because of its locations, of course. It made its mark in TV history because, in Robert Culp’s pro tennis player/secret agent Kelly Robinson and Bill Cosby’s fitness trainer/secret agent/sidekick Alexander Scott, it showed a white man and a black man in leading roles — equals — in a primetime TV drama that reached into virtually every home in America.

This was 1965, remember, when President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law, on Aug. 6 — a landmark piece of US federal legislation designed to prohibit racial discrimination in voting. I Spy bowed just seven months after civil-rights campaigner Malcolm X was assassinated in Harlem, New York. It debuted just six months after the civil-rights march on Montgomery, Alabama from Selma, and just 35 days after the riots in Watts, Los Angeles.

Cosby was just 28 at the time; Culp was 35. Cosby was of matinee-idol age, an instant TV star, a hero to millions and a role model, it’s not hard to imagine, to an entire generation of young African-American men and, arguably, women, too.

An actor simply reads his lines and hits his marks, of course; the real credit for the character’s creation and inception belongs to Culp himself, producer Leonard, and series writers David Friedkin and Morton Fine. (Culp came up with the initial idea of a James Bond-type secret agent tailored for TV and showed it the script to his friend Carl Reiner, who suggested he meet Leonard, who was then developing a spy drama of his own for TV. Culp’s name appears as the sole writing credit on the pilot episode “So Long, Patrick Henry,” which kicked off the series on Sept. 15 of that year. The pilot episode was directed by Leo Penn.)

Even so, much of what made Alexander Scott memorable was Cosby himself — his presence, his physical bearing, his line readings, the way he held himself and carried himself. (Interestingly, the script called for Cosby’s character to be an older man and mentor to Culp’s dashing but impulsive tennis pro-cum-secret agent; the story goes that Leonard saw the young Cosby perform a stand-up comedy routine at a Los Angeles comedy club and decided then and there to cast Cosby in the role, despite initial misgivings from both the network and the producing studio.)

Culp may have created Alexander Scott on the page, and Friedkin and Fine molded him from there, but it was Cosby who brought the character to life for the millions of viewers who tuned into NBC on Wednesday nights from 1965 to 1968.

Even to the casual viewer, “Scotty” — black, young, fit, and hip — was clearly the brains of the pair. Scotty was a renowned linguist who was marking time by hanging out with international playboy and tennis ace Kelly Robinson. Over the course of the first season, Scotty’s murky past — a string of covert activities for the US government — slowly came to light. It became general knowledge, among I, Spy viewers if not the semi-regular sidekick and recurring characters in the show, that Scotty worked for a clandestine arm of the Pentagon. Robinson hailed from an upper-middle-class background and had the means to support himself as an athlete and tennis bum — hot-tempered, impulsive and an unapologetic womanizer. Scotty, on the other hand, was aesthetic and studious, calm and collected, guided by moral principle and the holder of a black belt in judo, just in case a miscreant needed a more immediate, physical re-education. Scotty brought a certain gravitas to the relationship, a gravitas Kelly Robinson clearly lacked.

And yet, and this is where I, Spy proved unique, the closer one looked, the more their differences appeared to be minor compared to what they shared in common. The hidden message wasn’t so hidden, it turned out: I, Spy didn’t just talk about judging a person not by the color of their skin but by the quality of their character. I, Spy showed it, week in and week out, and broadcast it straight into people’s living rooms.

In the age of Malcolm X, the Voting Rights Act, Selma, Alabama and the slowly growing, inexorable, intractable conflict in Vietnam, it’s almost impossible to calculate today the effect Cosby and I, Spy must have had on TV audiences of the day. In I, Spy’s early years, Cosby was a pioneer, a role model in a trailblazing show.

I Spy was made at a time when light-hearted fare like Bonanza, Gomer Pyle USMC, The Lucy Show, and Batman topped the TV charts, but the TV program it reminds me most of today is Homeland.

That’s why the squalid drama surrounding Cosby today makes it so hard to square that circle.

Is it possible to watch I Spy today and appreciate it quite the same way, knowing what may well have been going on behind the scenes? The testimony that emerged at the Cosby trial suggests that his transgressions were not a one-off but rather a pattern of behavior, consistent over time and, yes, dating back to the mid- ‘60s and ‘70s.

I actually do think it is possible to watch I Spy today and appreciate the character — and the show — for what it was, and what it represents today.

I’d be lying, though, if I said I didn’t have qualms, a hard-to-explain unease. The movies are one thing — Harvey Weinstein, Kevin Spacey, Roman Polanski, the list goes on — but TV is more intimate, somehow, and so the betrayal runs deeper. Movies have always been made on a grand scale — I Spy was inspired in part by the James Bond movies, after all — but TV is the medium we invite into our homes, where it becomes part of the furniture and, in special cases, part of the family.

I imagine I will watch those old I Spy episodes again, one day.

When, and how, and under what circumstances, though, I can’t exactly say.

I suspect I’m not alone.